A pair of storms is vexing forecasters in a messy Atlantic, and one could make landfall on the U.S. coast as soon as Monday.

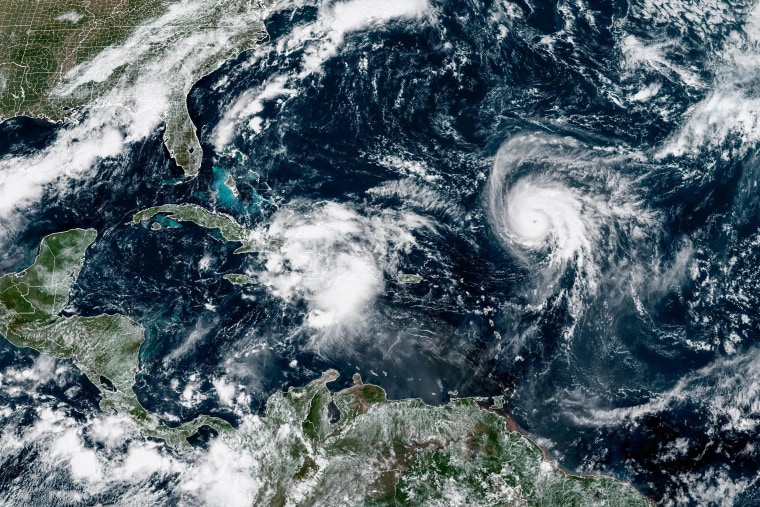

Two storms — Hurricane Humberto and a brewing disturbance called AL94, for now — are roughly 800 miles away from each other as of Friday morning.

Because the two storms are so close, they are subject to each other’s influence and a phenomenon called the Fujiwhara effect.

“It’s a very complex problem. It doesn’t happen that often to get two storms this close together — especially two strong ones,” said Andy Hazelton, a hurricane modeler and associate scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies at the University of Miami.

The Fujiwhara effect describes when two storms are rotating in the same direction close to each other around a shared midpoint. Sometimes, the weaker of the two storms is subsumed by the stronger storm or the two merge. Other times, the two storms orbit each other before spinning off on individual tracks.

Humberto is expected to become a Category 4 hurricane by early Monday, but hurricane modeling suggests it will stay out at sea, passing the Bahamas and remaining far away from the Eastern Seaboard.

AL94 has a 90% chance of becoming a tropical cyclone, according to the National Hurricane Center. Storms get names when their wind speeds reach 39 mph or higher. The disturbance will be named Imelda if it reaches that threshold.

“I think a hurricane is possible and something the Carolinas should look out for,” Hazelton said.

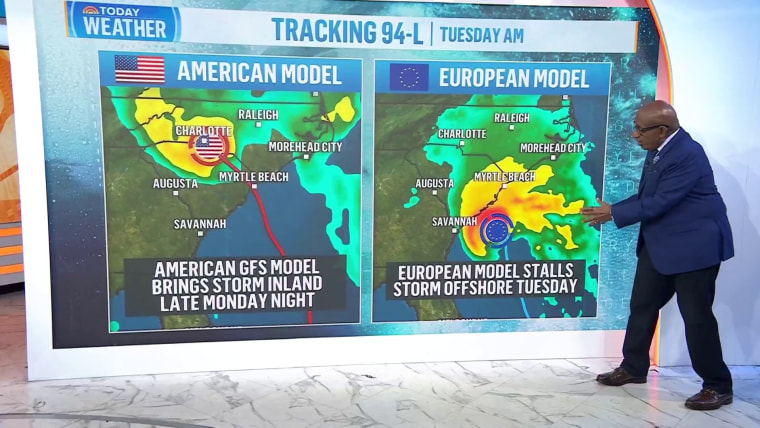

The storm’s track remains uncertain and probably won’t be more clear until the weekend. Some models suggest the storm could trend toward the Carolinas, only to have Humberto pull it out to sea in a hard rightward turn before it reaches shore.

Other models suggest Al94 will trend toward the coast and make landfall Monday. The system could stall over the Southeast and cause flooding concerns.

“While there is significant uncertainty in the future track and intensity of the system, the chances of wind, rainfall and storm surge impacts for a portion of the southeast U.S. coast are increasing,” the hurricane center wrote in an update Thursday afternoon.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecasters in May predicted an active Atlantic hurricane season with more storm activity than in an average year. NOAA’s forecast was in line with most other public forecasts from universities and private companies, according to a prediction-tracking website operated by Colorado State University and the Barcelona Supercomputing Center.

Hurricane season begins June 1 and ends Nov. 30. It typically starts to peak in late summer and early fall. Through Wednesday, activity was below most forecasting groups’ expectations.

Sea surface temperatures are about 1 degree Fahrenheit above normal in the North Atlantic, according to the University of Maine’s Climate Reanalyzer. Warm water can fuel hurricanes and cause them to intensify more rapidly than they would in colder conditions.