A federal judge Monday ruled that the Trump administration wrongly removed slavery memorial panels that were placed at a historical Philadelphia site in 2002. The decision came after the Black activists who pushed the city to place the panels again organized in support of their presence last month.

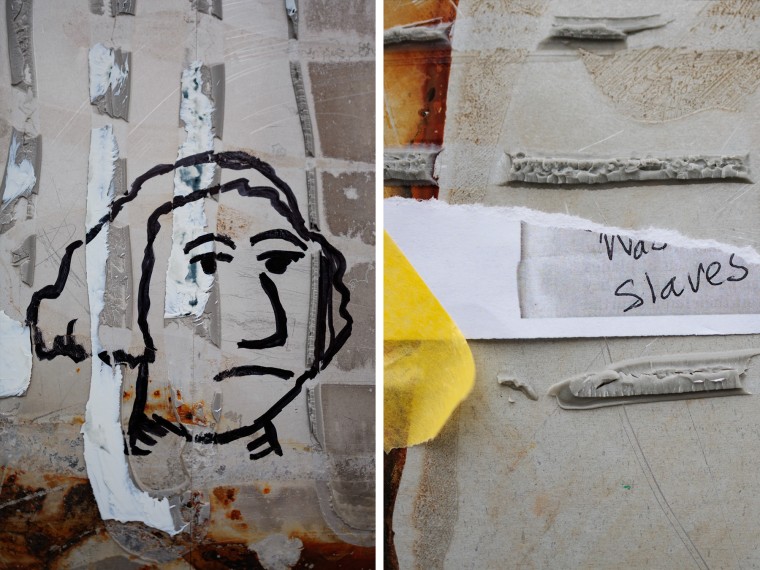

The National Park Service removed several panels from the President’s House in Philadelphia, citing a March 2025 executive order by President Donald Trump to prohibit exhibitions or programs at federal sites based on race. President’s House features exhibits about George Washington and among the 34 historical panels, 13 were created after a group of activists lobbied the city and the park service to include information about the nine men, women and children who were enslaved by Washington there.

U.S. District Judge Cynthia M. Rufe granted a preliminary injunction on Monday requiring the return of the panels, pending further litigation.

“We battled for eight solid years the grand opening of the first slavery memorial of its kind on federal property in the history of the United States of America,” attorney and activist Michael Coard told NBC News before the judge's ruling. “What started me to do this was anger and rage and outrage.”

The movement began in 2002 when the park service and the city of Philadelphia announced the Liberty Bell would move from a pavilion facing Independence Hall to 6th Street and Market Street, the same location of George Washington’s executive residence where he enslaved at least nine people, including children.

Coard hosted a radio show on WHAT, during which he told listeners that the site was planned without a clear acknowledgment about the enslavement that took place there. It spurred the Avenging The Ancestors Coalition, which protested and raised funds — along with the city government — to pay for panels at the site.

The memorial opened Dec. 15, 2010.

Coard said his organization anticipated what was in store after the executive orders Trump signed upon returning to office last year. The panels were unceremoniously taken down a few weeks ago on Jan. 22.

“The common denominator of the 13 was that they highlighted the horror of slavery,” Coard said of the panels. “Not just what we all know — a loss of freedom — but the beatings, the whippings, the rapes, the sodomy.”

A spokesperson for the Interior Department, which oversees the park service, said “all federal agencies are to review interpretive materials to ensure accuracy, honesty, and alignment with shared national values.” White House spokesman Davis Ingle said Trump “is ensuring that we are honoring the fullness of the American story instead of distorting it in the name of left-wing ideology.”

Last week, more than 200 activists, residents and supporters protested the panels’ recent removal.

The rally attracted people across political ideologies and ethnicities, said Gerry James, 36, who traveled to the event from Frankfort, Kentucky. James is the deputy director of the Sierra Club’s Outdoors for All campaign, which is working with Avenging The Ancestors Coalition.

He said his parents often took him and his siblings to libraries and cultural tours to learn more about Black history, aside from the limited information that was present in his textbooks.

“It’s just a lot of support for this issue of preserving Black history and preserving Black history as American history,” James said.

Supporters pushed back against the administration’s moves toward downplaying “our complex national history,” specifically when it comes to Black American history.

Mijuel Johnson, a steering committee member of the coalition who also spoke at the rally, said the panels “are not just panels” but serve as a national memorial: “The very fact that this is a memorial to the enslaved people of the United States,” and one of the first of its kind on federal property in the United States, he said, “is significant.”

Coard’s group — headed by University of Pennsylvania law professor Cara McClellan and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund — joined the city’s lawsuit against the park service’s acting director and the Interior Department.

“One, we’re demanding restoration — put the 34 interpretive panels back where they were,” Coard said before the ruling. “Two, we’re demanding enhancement, which means to expand this President’s House slave memorial site. And number three, we’re seeking replication. We know that Black people have contributed mightily in every state in the country and maybe even every city in the country, so we want something like this on any federal property throughout the United States where Black folks were enslaved.”

He and other activists are optimistic about the future of the site.

“We are passionate about this,” Coard said, “and we’re going to win this fight.”