A fruit seller and father of two killed during his first protest. A biotechnology graduate with a passion for art who bled to death in her father’s arms. A distraught family ordered to pay morgue officials $7,000 for a loved one’s body unless they lie and say their relative died at the hands of anti-government rioters.

These are a tiny fraction of the thousands of Iranians killed or wounded when the government cracked down on protests a month ago. With the nation still reeling, details about victims are trickling out and the world is gradually getting a clearer picture of the violence used to suppress the nationwide demonstrations.

Most of the killing happened during a two-day period between the night of Jan. 8 and Jan. 10, with over 7,000 people killed across the country, according to the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency.

“This was a very rapid 48-hour massacre. I can’t think of anything in Iran’s own history that’s comparable, unless I go back to the 18th century,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran, a New York-based advocacy group.

The demonstrations, sparked in late December as the rial currency crashed and inflation soared, turned into one of the biggest challenges faced by the Islamic Republic in its 47-year history as thousands of people across the country, including members of the country’s many ethnic minority groups, took to the streets to demand an end to clerical rule.

Communicating with journalists can be very dangerous for protesters’ families, and Iran is in the middle of a communications blackout with severe restrictions on the internet and cellphone service. So to report on those killed by security forces, NBC News relied on sources outside Iran who were in touch with the families of victims inside the country.

These are the stories of four killed during January’s carnage.

Negin Ghadimi

Negin Ghadimi studied biotechnology, but her real passion was art. In a video posted on Instagram, 26-year old Ghadimi shows a sketch of a woman’s dress covered with mirrors that she has designed. She wanted people to see their own reflections, she said.

“My view of my future is very bright,” Ghadimi, a former competitive swimmer, says in a separate Instagram video.

She lived in the city of Sari in northern Iran and would sometimes visit family in Tehran, according to a relative who is not being identified for security reasons. “She was full of life, loved nature, loved art,” the relative said in a telephone interview.

On Jan. 9, Ghadimi’s family decided to attend a protest while on a visit to Tonekabon, a small city in northern Iran on the Caspian Sea.

“I told her, ‘Baba, dear — you stay. Don’t come. I'm going out,’” Ghadimi’s father says in an Instagram video of a commemoration ceremony for her, his voice cracking.

“She said, ‘No my dear, I’m coming to look out for you.’”

When Ghadimi and her family arrived at the protest, security forces began shooting tear gas at the crowd and the family was separated, her relative told NBC News. Again, Ghadimi’s father tried to get her to leave, the family member said.

Ghadimi and her father were holding hands as they walked with other protesters when security forces began shooting at an intersection. A bullet hit the side of Ghadimi’s body.

Ghadimi told her father she was burning, the source said.

Her father screamed for help and laid her on the ground, the family member added. Soon a crowd gathered and helped carry Ghadimi into a nearby house.

Ghadimi licked her lips over and over. Her shoes were covered in her own blood, according to the relative.

Nearby, the shooting continued unabated as Ghadimi’s father, who had been shot in the hand with pellets, begged for help to get her to a hospital, according to her relative.

After around 45 minutes, a woman driving a car past the house stopped and agreed to take a heavily bleeding Ghadimi to the hospital. The medical staff tried to revive her, but it was too late.

“She lost her life in my arms, but I couldn’t do anything for her,” her father says in the Instagram video of the commemoration ceremony.

On Ghadimi’s death certificate, a copy of which was seen by NBC News, her cause of death is listed as “Impact from a high speed projectile object to the body,” rather than being shot by a bullet which would ordinarily be noted.

“It’s ridiculous,” her relative said.

Ghadimi’s body was taken to Behesht-e Zahra, Iran’s largest cemetery, located about 5 miles south of Tehran’s southern suburbs, for burial. Nearby, crowds chanted anti-government slogans, her relative recounted.

Yasin Mirzaei Ghalazanjiri

A geophysics graduate student, Yasin Mirzaei Ghalazanjiri was studying in Italy when he decided to visit family in Kermanshah, a city in western Iran home to a large population of fellow ethnic Kurds, during his New Year’s university break. He joined friends and family at a large protest in Kermanshah on Jan. 8.

It did not seem dangerous at first, but that changed quickly. Ghalazanjiri was shot in the chest by a sniper bullet and died on the spot.

“When they shot Yasin, his family and friends were around him,” said a relative, who asked not to be identified because he was afraid Iranian security forces would harass or harm him outside the country or his family inside Iran.

“They wanted to take his body so it wouldn’t be grabbed by security forces. But at that same time, another one of our family members was shot in the face with pellets,” he added during a telephone interview.

The group decided to pull the wounded man to safety before going back for Ghalazanjiri’s body. By the time the gunfire had subsided, Ghalazanjiri had disappeared.

When family tried to find the body at the city morgue, they encountered rows and rows of unzipped body bags.

The security forces at the morgue gave the family a choice: either say that Ghalazanjiri was killed by “rioters” among the protesters or pay 700 million toman, approximately $7,000. They called it “haq-e tir,” or bullet price.

The family refused to accept the version of events pushed by the authorities and paid the money to get the body back. Even though the family paid, the security forces said they should keep quiet about the circumstances of his death or else they would rebury Ghalazanjiri in an undisclosed location.

A crowd showed up for Ghalazanjiri’s burial at a family plot in a rural area outside Kermanshah and chanted anti-government slogans despite the threats, according to his relative.

On Jan. 15, the rector of the University of Messina, where Ghalazanjiri studied, expressed her condolences at a gathering of students, and Ghalazanjiri’s picture was placed on an empty chair.

The entire family is heartbroken by the loss of a vibrant young man who had so much potential, his relative said.

“It’s not only Yasin. Anytime we see the protest videos, it makes us cry,” the relative said. “We’re human after all. We’re agonizing for everybody.”

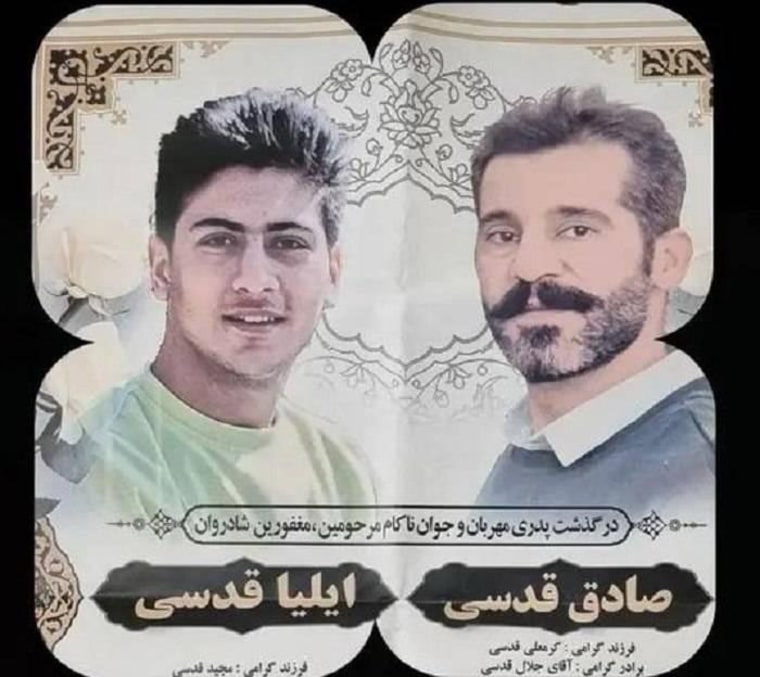

Sadegh Ghodsi and Ilya Ghodsi

Sadegh Ghodsi, a 38-year-old Tehran fruit seller, was not politically active. But on Jan. 8, the father of two decided to attend a protest with his cousin’s son Ilya, 17, according to a source close to the family.

They were among other protesters in the Qaleh Hassan Khan neighborhood in western Tehran when security forces opened fire on the crowds, he said on condition of anonymity out of fear that Iranian security forces would harm him or his family.

Both were killed.

The family searched desperately for their bodies and eventually found them at the Kahrizak Forensic Medical Center south of Tehran. Videos that have leaked out of Iran and were verified by NBC News show rows and rows of body bags inside and outside the facility as families try to identify their relatives.

When family members found the bodies of Sadegh and Ilya, the authorities would not allow them to be removed. They, like other families, were offered a choice: pay a bullet price of 800 million toman, or about $8,000, or sign a document stating the two were members of the Basij, a paramilitary force overseen by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, who were killed by “terrorists.”

“They didn’t have the financial resources to pay. They didn’t have a choice, so they accepted,” the source close to the family said in a telephone interview.

“When the family received the bodies, there were so many other bodies they were only given half an hour in the mosque for a funeral service,” he added.