A liberal lawyer was elected president of South Korea on Tuesday, ending months of political instability in the key U.S. ally that began with a botched declaration of martial law.

Lee Jae-myung, leader of the Democratic Party, was sworn into office Wednesday. His conservative rival, Kim Moon-soo, of the People Power Party, said he humbly accepted “the choice of the people.”

According to the National Election Commission, Lee received 49.4% of the vote, while Kim received just over 41%. Another conservative candidate, Lee Jun-seok of the upstart Reform Party, received 8.3%.

In his inauguration speech, Lee, 61, emphasized national unity after the martial law episode and said he would be “a president who ends the politics of division.”

“We will fully uncover the truth, assign proper responsibility and establish firm measures to prevent recurrence,” he said.

Lee said he would lead a “pragmatic, market-oriented government” and strengthen U.S.-South Korea relations and trilateral cooperation with the U.S. and Japan.

In a departure from his predecessor, Lee also said he would engage in dialogue with rival North Korea while responding strongly to its nuclear and military provocations.

“We will restore the military’s honor and the public’s trust, which were damaged by illegal martial law, and ensure that the military is never again mobilized for politics,” he said.

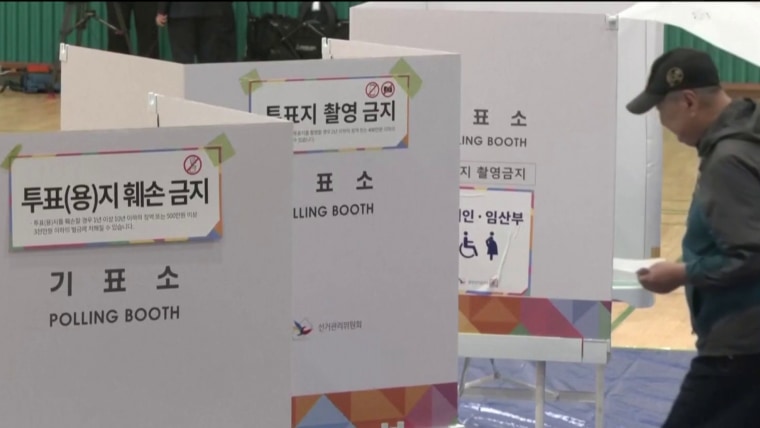

The election took place six months to the day after President Yoon Suk Yeol shocked the East Asian democracy of more than 50 million people by abruptly declaring martial law, citing threats from “anti-state forces” and accusing the opposition-controlled parliament of paralyzing the government.

Lawmakers pushed past soldiers Yoon had sent to parliament to vote unanimously against the order, which Yoon then withdrew.

Led by Lee, lawmakers impeached Yoon on Dec. 14 over the short-lived order, after which South Korea was led by a series of acting presidents. The leadership vacuum has hampered South Korea in Washington as it is trying to negotiate with the Trump administration over a 25% “reciprocal” tariff and other levies.

Lee, who narrowly lost to Yoon in 2022, had been considered the most likely next president since Yoon was impeached. The election was triggered in April when the Constitutional Court upheld his impeachment.

But South Korean voters were animated more by anger at Yoon and his party than by an affinity for Lee.

“His victory is not thanks to any particular policy proposals, but rather a result of Yoon’s spectacular collapse,” said Leif-Eric Easley, a professor of international studies at Ewha Womans University in Seoul.

The martial law episode has deeply unsettled South Korea, which spent decades under military-authoritarian rule. It has also worsened polarization between liberals and conservatives, with regular rallies held for and against Yoon and a presidential campaign filled with personal attacks.

Some voters directed their anger at Kim, the candidate for Yoon’s former People Power Party, even though Yoon left the party last month to help his campaign.

“I believe that Lee will restore the democratic system and establish a democratic government,” said Lee Jung Sup, a company executive in Seoul. “Then our economy will be revitalized.”

Kim, who was labor minister under Yoon, criticized the martial law declaration but opposed his impeachment. Supporters pointed to Kim’s squeaky-clean record, contrasting it with Lee’s involvement in several criminal trials.

“It is unfair to reflect the martial law declared by the former president onto Kim,” said Oh Chang-soo, a retired religious leader in his 60s.

Lee’s vows to punish those involved in the martial law order have raised fears of further political turmoil. Yoon is still standing trial on charges of insurrection, a crime that is punishable by death or life in prison.

Lee said this week that besides addressing economic concerns and internal division, his main priority is reaching a trade deal with the United States.

In addition to the 25% tariff — which is set to take effect July 9 —South Korea’s trade-dependent economy is vulnerable to sector-specific U.S. levies on some of its most important exports, such as steel and automobiles.

Asked about President Donald Trump’s tendency to pressure his negotiating partners, Lee said, “That’s a kind of political behavior exhibited by powerful nations, and we must endure it well.”

“If the president of the Republic of Korea’s kowtowing briefly would allow 52 million people to thrive, then he must do so,” he told South Korea’s Christian Broadcasting System on Monday, using the country’s formal name.

While Trump is a formidable figure, Lee said, diplomacy should be mutually beneficial, and “I’m not an easy opponent, either.”

“We have a fair number of cards to play,” he said. “There are things to give and take on both sides.”