Federal immigration agents flooding U.S. streets are using a new surveillance tool kit whose increasing use on observers and bystanders is alarming civil liberties advocates, lawmakers and activists.

Using smartphones loaded with sophisticated facial recognition technology, in addition to professional-grade photo equipment, agents are aggressively photographing faces of people they encounter in their daily operations, including possible enforcement targets and observers. Some of the images are being run through facial recognition software in real time.

The use of these tools and tactics is setting a new standard of street-level surveillance and information collection that has little precedent in the U.S.

In recent months, Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other Department of Homeland Security officials have photographed and scanned Americans in Minneapolis, Chicago and Portland, Maine, often without their consent.

Though smartphone, surveillance and doorbell cameras make it increasingly difficult to participate in almost any aspect of modern life without being recorded, the new DHS tactic is an unprecedented escalation in how the federal government tracks people, including U.S. citizens, according to lawmakers, civil liberties advocates and activists.

“The idea that law enforcement is using mobile facial recognition on the streets is shocking,” Andrew Ferguson, a professor of law at George Washington University who focuses on police technology, said of the scannings. “Largely because there was a sense that such technology was neither ready for prime time, nor acceptable in a free society,” Ferguson said.

NBC News verified more than a dozen videos in which immigration officers appear to be photographing the faces of people they encounter, either with phone or professional cameras, multiple witnesses of immigration enforcement action also told NBC News that their faces were captured by federal agents. While DHS has said facial recognition scans are meant to assist with immigration enforcement, several people photographed by officers described it as an act of intimidation.

Do you have a story to share about DHS surveillance? Contact reporter Kevin Collier on Signal.

In many of the cases, it’s not clear if or when facial recognition technology is immediately being used in the field, but the practice has been acknowledged by DHS and by photographers who have captured the technology’s interface on the phones of agents using it.

DHS may hold some of the photos for 15 years and no one can opt out of being scanned, according to department documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by the tech news site 404 Media.

The growing surveillance activity on Americans comes as DHS, under which Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement operate, has invested heavily in AI-assisted facial recognition technologies that can rapidly compare an uploaded photo with vast databases to make a likely match, according to an NBC News review of publicly available agency contracts and a document reviewing its AI tools.

Many of the photos are taken through a customized DHS smartphone app called Mobile Fortify, which debuted last year. After a person’s face is scanned, the app is supposed to rapidly identify the individual and present their biographical information to the DHS employee using the technology, according to a document the agency published last week in accordance with executive orders signed under presidents Joe Biden and Donald Trump.

A DHS spokesperson said in an emailed statement that Mobile Fortify is designed to quickly identify persons of interest for the agency.

In other cases, immigration agents have photographed activists’ faces with professional-grade cameras, according to videos and firsthand accounts given to NBC News. Agents did not give notice or explanation for why they were photographing the activists, who suspect it could be an intimidation tactic.

It’s not clear that the practice violates any federal law. But two sweeping lawsuits have alleged that the scans are part of a larger practice of ICE violating people’s rights.

The office of Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul claims that the app has been used more than 100,000 times since it debuted last year, and alleges that the facial scans violate the Fourth Amendment right to privacy from government searches without a warrant.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Minnesota has also filed a class action lawsuit against ICE and CBP, alleging that their officers engage in a range of illegal practices and that forced facial scans have become routine.

In an emailed statement, a DHS spokesperson said, “Claims that Mobile Fortify violates the Fourth Amendment or compromises privacy are false.”

“Mobile Fortify has not been blocked, restricted, or curtailed by the courts or by legal guidance. It is lawfully used nationwide in accordance with all applicable legal authorities,” the spokesperson said.

On Wednesday, Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., introduced new legislation that would ban ICE and CBP’s use of facial recognition technology. In September, he and eight other Democratic Senators wrote an open letter to DHS Secretary Kristi Noem asking for more details on how Mobile Fortify works and how it will safeguard information collected by the app. They have not received a response, a spokesperson for his office said.

The DHS spokesperson did not respond to other questions about the app’s scope or what the agency does with photos it took of people not suspected of being in the country illegally.

Scanned on the street

During recent operations, ICE agents have been routinely spotted holding their smartphones to people’s faces in what appear to be attempts to verify people’s citizenship.

In a video taken by a resident in the Chicago suburb of Aurora last fall, ICE agents pull over two young men riding their bikes in a residential neighborhood. One agent asks the young men, “Can you do facial?” before holding his phone up to each man’s face. He tells one of the men to “look right here” into the camera.

In another video, taken in Forest Lake, Minnesota, agents confront a man and ask for his citizenship status, with one holding up his phone and telling the man to remove his hood.

Steven Young, a 41-year-old Minnesotan lawyer who habitually observes ICE operations in the Minneapolis area, said he has repeatedly seen agents holding their phones to people’s faces.

On the morning of Jan. 21, he said he witnessed ICE agents setting up checkpoint for cars, and during the stops, several agents held their phones to the occupants’ faces.

“From about half a block back I saw them leaning into car windows, scanning people’s faces,” Young said.

Mubashir Khalif Hussen, an American citizen detained by ICE in December and whom the American Civil Liberties Union is representing in a lawsuit against ICE and DHS, claims agents repeatedly tried to scan his face.

“I was terrified of what they were going to do with a picture of me, and I did not trust them. I would not let them take a picture of me,” Hussen said in a statement sent to NBC News through the ACLU.

“The officers also kept telling me that they were going to ‘take me in’ if I did not let them scan my face,” he said. Hussen did not consent to the scan and was detained by the officers.

Local politicians in Maine and Minnesota said they have received multiple complaints of ICE documenting residents’ faces.

“I’ve heard reports that agents are taking photos of people, even when they aren’t the subject of enforcement action,” said Carl Sheline, the mayor of Lewiston, Maine.

“Given ICE’s tactics and our government’s slide into authoritarianism, I’m alarmed. This definitely has a chilling effect and I’m worried that this will be used to silence dissent.”

Erin Maye Quade, a Minneapolis state senator, said she was baffled by the reported tactics of ICE tracking “commuters and constitutional observers.”

“They take pictures of cars’ license plates and then people’s faces, and they’ll take videos,” Maye Quade said.

“We had a parent who was making sure the bus stop was safe in her neighborhood. ICE was parked maybe 50 feet away from the bus stop, and she parked and was waiting to make sure that it was safe for the kids. One of the ICE agents climbed into the back of his own JEEP and then was filming her while she was making sure kids got on the bus safely,” she said.

That might be “a little bit harder to identify as being face recognition, but I don’t really know what else it’s for,” Maye Quade added.

More than immigration enforcement

The DHS practice of scanning faces goes beyond verifying whether someone’s the target of a criminal investigation, according to some observers and activists, who say agents have used surveillance as a form of intimidation.

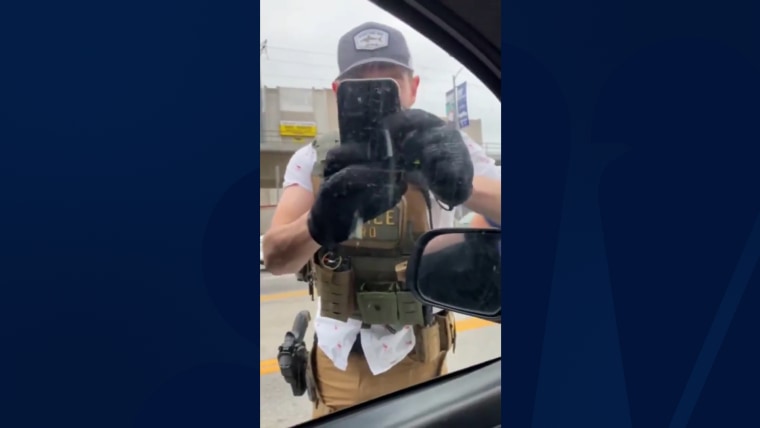

In January, Katie Henly, a Minneapolis mother, repeatedly went on “patrols” with neighbors to follow and observe immigration officials’ vehicles in and around her neighborhood. In an incident she captured on video, the car she was following suddenly stopped. Armed agents poured out, as well as a man wearing a CBP vest, who said nothing but pointedly took photos of her licence plate and her face through the window.

“I just kind of felt like, OK, I am known,” she told NBC News. “I cannot hide anymore. I felt like I was pushed into a new category in the resistance movement.”

“Previously, I was just like, standing watch at the corner of my kids’ elementary school and donating money,” Henley said.

Skye, a Minneapolis woman and retired Marine who requested her last name not be published, similarly followed a car of ICE agents in January. A video taken by her friend shows agents violently pulling her from her car. Skye told NBC News she was detained for about five hours and that, after she returned home, when she left her house to walk her dog, an ICE agent followed her and took photographs of her.

“He didn’t say anything. I just heard the click, click, click, click of his phone,” she said. “It felt like intimidation and retaliation for me just exercising my constitutional rights that I f- — -ing fought for,” she said.

When Alex Feinberg took a video of masked ICE agents at a gas station in Portland, Maine, in January, one of them pulled out his phone and documented him in turn.

“They didn’t say anything. The one guy in the video that you can clearly see took my picture just whipped out his phone, pointed it at me, and then put it away fairly calmly,” he said.

DHS did not respond to emailed questions asking what the purpose of taking such photos is or how they will be stored or used.

Some administration and immigration officials have indicated that people who protest or observe their operations can be put on a watchlist.

White House border czar Tom Homan said on Fox News on Jan. 15 that “we’re going to create a database where those people that are arrested for interference, impeachment, assault; we’re going to make them famous.”

In a video a Maine woman posted to social media in January, an ICE agent tells her that “we have a nice little database” and “now you’re considered a domestic terrorist.”

Tricia McLaughlin, a DHS spokesperson, seemed to deny that in an emailed statement, in which she said “There is NO database of ‘domestic terrorists’ run by DHS.”

A new use for emerging technology

At its core, facial recognition technology is straightforward: It compares an image with a library of other images and determines the likelihood that two images show the same person.

Like fingerprint or retinal scans, facial recognition is considered a form of biometric surveillance. Privacy advocates caution that it can be particularly invasive because many biometrics markers are permanent and can’t be changed if a person wants to stop being identified. Biometric technology can also make mistakes and has been criticized for finding false matches, especially with people of color, and has, in some cases, resulted in police arresting the wrong person for a crime.

In recent years, the use of biometric technology has spread. Stores increasingly use it to track customers suspected of shoplifting, entertainment venues deploy it during big events, and many cellphones give users the option to unlock their devices with an instantaneous face scan.

Facial recognition tools have also become widely available to law enforcement agencies across the country, but there was a time when they were largely used as investigative tools, using photos of individual suspects rather than proactively scanning people in the field.

With the exception of air travel, Americans have not previously had their faces routinely scanned by the government.

Much of the publicly available information about Mobile Fortify comes from an internal report on the app, called a Privacy Threshold Analysis, obtained by the tech news site 404 Media. 404 obtained it through a Freedom of Information Act Request after first breaking the news of the app’s existence.

CBP and DHS did not respond to NBC News questions about the internal report on Mobile Fortify.

According to that document, once the the photo is taken with Mobile Fortify, the app quickly compares it against three databases: a database of CBP targets, CBP’s library of valid travel documents like passports and drivers’ licenses, and a third category that is redacted.

ICE also has two contracts with Clearview AI, a facial recognition company that scours social media and maintains a giant database of photos. The contracts are for a combined $6 million, according to USA Spending, a site that tracks government contracts.

According to a document on DHS’s use of AI published in January, as of last year Clearview had only “been deployed in a limited test or pilot capacity.” Clearview did not respond to a request for comment.

Quade, the Minnesota state senator, said opposition to DHS surveillance should come from both sides of the political spectrum.

“I think that there’s something very unifying between the right and the left of not wanting to be surveilled by their government,” she said.

“We deserve to move freely throughout our country, our state, without being scanned against our will and our faces stored by our government.”