PARK CITY, Utah — From the edge of Dan and Amy Macuga’s backyard, the view sweeps south, down a hillside, across a valley traced by Interstate 80 and up into the mountains surrounding Park City.

From here, even miles away, a bald patch of one mountainside can be seen clearly. Carved into the mountain is Utah Olympic Park, a competition venue that was built when Salt Lake City hosted the 2002 Olympics. The venue is still a year-round training facility, as athletes from the U.S. national ski and snowboarding team fly off its towering twin ski jumps and use its deep-water pools and air bags to practice tricks.

The Macugas moved to Park City in 2007 to follow Dan’s marketing career. In hindsight, their decision to live in this house, with this view of and proximity to Olympic Park, might seem part of a long-term plan to inspire and nudge their three daughters and son to where they are now — among the world’s best athletes on skis.

Sam, 24, is a ski jumper; Lauren, 23, is a downhill skier; and Alli, 22, competes in moguls. Their 20-year-old brother, Daniel, is also a competitive skier.

At one point, the three eldest, sisters Sam, Lauren and Alli, all harbored legitimate aspirations of representing the U.S. at next month’s Milan Cortina Winter Olympics. Lauren had been expected to make the team following a breakout 2025 season, until she suffered a season-ending knee injury in November, while Sam and Alli were considered longer shots during this Olympic cycle.

Had all three sisters made the Olympics, it would have marked only the third time three siblings had qualified for the U.S. Winter Olympic team, according to past research by Bill Mallon, an Olympics historian. Still, ahead of the 2030 Olympics, the family could be the next big thing in U.S. skiing and would have a chance to become the first set of U.S. siblings to qualify in different disciplines.

All of it can feel predestined. That is, until you realize the only thing rarer than their world-class potential in multiple disciplines is how they achieved it — without a hint of a plan by either the parents or their children.

“It’s crazy if even just one of us goes” to the Olympics, Sam said in July. “This was never the goal.”

Overbearing parental expectations, pressure, burnout and specialization at an early age are hallmarks of an extreme youth-sports culture that values a future career in pro sports as its pinnacle. Making an Olympic team can be a lifelong pursuit commonly nurtured by parents who competed or coached in the sport.

And then there are the Macugas. When Sam, at 16, became the first sibling to make a U.S. national team, her mother’s first reaction was to ask for clarification. “What’s that mean?” Amy asked.

Eight years later, one evening last July, all six family members gathered for dinner on their back deck looking at the view of the mountains. It was one of their few days together in any given year, given their hectic athletic schedules. As they grilled vegetables and meat on portable tabletop grills, Dan and Amy gladly acknowledged they are still largely unclear about many of the rules governing their children’s disciplines.

“You guys just supported us. You never really, like, pushed us,” Sam said.

“Well, half the time we don’t even know what’s going on,” Dan said.

“Dad, how many points do judges score a ski jump out of?” Sam quizzed.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said.

“We stood at the finish line and heard parents just jump on their kids like, ‘No! That gate, you didn’t put enough inside pressure, blah, blah, blah,’” he continued. “I’m like, ‘Wow, the kid’s 9.’ It’s like, it’s just too much. We just kind of go with it and let it happen, and I think it’s more exciting that way.”

Different disciplines, same intensity

As recreational skiers, Dan and Amy wanted to live in Park City, about a half-hour’s drive east of Salt Lake City, to be closer to its plethora of runs and powder.

Dan came from a background in basketball, while Amy was a water skier, and their kids were encouraged to try any sports they liked. Though the children attended a Park City high school built to allow its students time to focus on winter sports — its calendar was reversed, placing “summer” vacation in the winter — they weren’t drawn to those sports at first. The Macugas played lacrosse. Alli played soccer until her sophomore year of high school. Had the family never moved from Texas to Utah, Sam said she likely would have become a swimmer.

“I would never have gotten into [skiing] if we hadn’t moved here,” Sam said.

Then the family signed up for Get Out and Play, a local program founded after the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics to let local children try a variety of winter sports. It’s where Sam, then 7 years old, learned to ski in 2008. It’s tempting now to believe that Sam, with the thin build of a ski jumper, was born for the event. Yet ski jumping was just one of many disciplines she tested, and like the others, it was picked on a whim because it simply looked fun. She stuck with it because she liked it, and when a club invited her to join, she said yes to that too. Early on, her parents watched a local competition as skiers flew off tall ramps, angled their bodies over skis and flew.

“We’re like, this is super cool! There’s no way she’s ever gonna do this,” Dan said. “And then when she did it, you’re like, ‘Huh, well, I don’t know how that happened.’”

Before Lauren focused on Alpine skiing, she tried ski jumping, too. Alli tried freestyle, big air, half-pipe and ski jumping before landing on moguls. Instead of thinking years down the road about what it might lead to, the family was only thinking months ahead. They didn’t buy skis for their children; they rented skis for years. Their kids had to abide by one rule: If they signed up for a sport, they had to commit to seeing the season through.

If their introduction to winter sports was happenstance, their path to becoming world-class athletes was not. The sisters can fit the stereotype of the chilled-out ski bum; Lauren is almost always wearing a multicolored bucket hat and socks with catchphrases from her favorite movie, the stock car satire “Talladega Nights.” Yet that affability contrasts with the competitive streak each has shown since they were toddlers, fighting over the color of their sippy cup. (Everyone wanted pink, Alli said.) When one sibling got a pet cat, suddenly the rest needed their own cats. Video games, like Mario Kart, have led to toppled living-room furniture.

It’s why competing in different disciplines was a conscious choice.

“I would absolutely lose it if any of them was doing moguls,” Alli said. “I don’t think I could handle that. I would get so pissed if they were beating me.”

During the family’s dinner last July, Dan turned and grinned mischievously.

“Watch this,” he said quietly, before addressing the table. “So, whose sport is the hardest?”

The siblings argued for the next minute. It would have been all right, her father later commented, if some of the siblings’ disciplines had overlapped.

“That would be a nightmare,” Lauren said. “It would be World War Macuga in this household.”

Not being pushed to cluster into one sport has reduced competition among the siblings and allowed the Macugas to freely chat with one another about their anxieties, stresses and successes without worrying it could cost them a spot on a podium. Within elite sports, not every athlete has such an outlet. The Macugas believe their strong bonds are an advantage.

The encouragement can be vital.

When Lauren won her first race in the prestigious Alpine World Cup in Austria in early 2025, she called Sam, who was in Norway, and told her she was flustered by the unexpected win and the attention that came with it. They talked it through, in a uniquely Macuga way. The siblings admit they don’t know the nuances of one another’s disciplines, but they can relate to the stress of navigating life as a professional athlete.

“I haven’t skied in the World Cup or done dual moguls,” Sam said. “But if you want to talk about being on the circuit, or having to travel so much, or dealing with the ski team, like, yeah, I got you.”

Others took notice after Lauren’s victory. Lindsey Vonn, the gold medal-winning U.S. skier, has said that “women like Lauren have so much potential and so much talent and work ethic.” Yet when Lauren tore a knee ligament in a fall during a November training run, it ended her Olympic ambitions in a year when winning a medal might have led to mainstream recognition.

“RIP acl,” she wrote on Instagram. Photos she posted later showed her wearing her trademark bucket hat in a hospital bed, post-surgery.

Alli has suffered numerous concussions, and a particularly damaging one in 2024 has led to symptoms that have lingered ever since, in what her doctors have diagnosed as post-concussion syndrome. She is back competing, but at her worst, she couldn’t focus enough to even hold a conversation.

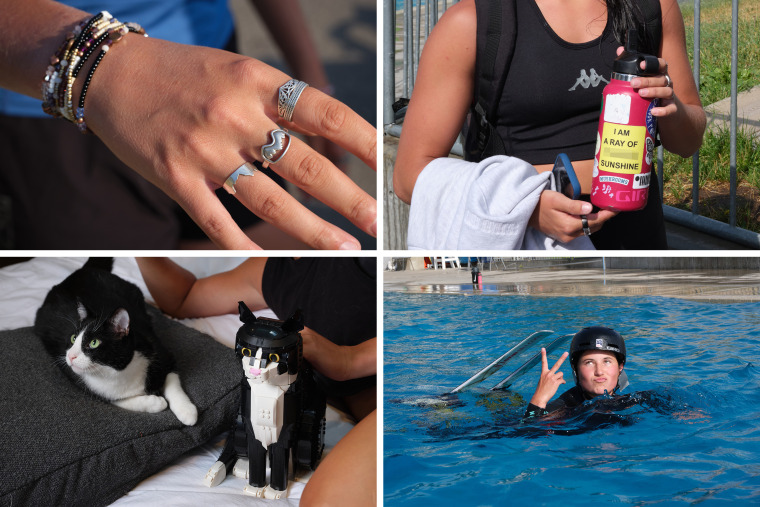

She leaned on her family for support. Their mother, Amy, has made her daughters bracelets featuring charms of skis and scarves. Each owns a silver ring cut into the shape of ski goggles and a mountain. They talk in concert — with a cadence so similar even teammates can find it difficult to distinguish who has said what — and work in tandem. When Lauren turned on a Black Eyed Peas song with thumping bass while in her Jeep on a warm night last summer, Sam reached to turn up the volume. They were headed home from Utah Olympic Park, where they had watched Alli perform in a trick show.

In the front row, poolside, Alli’s parents and siblings had sat whooping and cheering.

“People are like, ‘You really get along this well?’” Amy said. “And we’re like, ‘Yeah!’”

Never together, always close

When Dan and Amy Macuga’s children seemed intent on going into winter sports, the parents offered what they thought was a low-stakes incentive.

Make the national team, and we’ll buy you a car.

“Thinking, why on earth would they ever make the U.S. ski team?” Dan said.

Their garage now includes three Jeep Wranglers, one for each sister, and a Jeep Gladiator that Daniel earned when he reached certain benchmarks. The kids no longer rent their equipment, but get it provided by sponsors, which means that six sets of nearly every piece of ski equipment are stored in the family’s garage.

“It’s like Big 5 Sporting Goods blew up in this place,” Dan said.

Little of what is stored there gets much use, though. The travel required for training and competition is so intense and constant that Lauren, Alli and Daniel have all opted against going to college. Sam is studying engineering at Dartmouth, but she attends only one academic quarter per year as part of what she calls her “12-year plan.” The family spends only a few weeks together annually. In July, their mother was calculating how much time the entire family would have together in Park City. It was about 72 hours.

Tracking everyone’s crisscrossing whereabouts has proved so hectic that Amy uses a spreadsheet. It’s not a perfect system. Sam recalled a time last year when Daniel flew into Salt Lake City and asked the family’s group chat who was picking him up for the 30-minute drive home. No one else was even in the country.

“We’re never together,” Sam said. “But we’re all super close.”

This kind of lifestyle isn’t appealing or even feasible for every family. The Macugas don’t consider themselves a model for others. Partly because there still is no model.

Using his background in marketing, Dan tries to help his daughters as they “build a brand” on social media, which is a necessity in a sport where sponsorship dollars aren’t plentiful and making a living can be difficult. Amy, their mother, helped create a “Team Macuga” logo. As a side hustle, Sam manages social media for some fellow athletes and picks up shifts as a server at a Park City restaurant when she is back in town.

Their parents are bewildered that Lauren receives mail from ski-obsessed fans in Europe almost daily. When Sam and Alli spoke at a U.S. Olympics media event in New York City in October, their parents smiled from one side of the dais, as if looking for someone to pinch them.

“The coolest part is they were never pushed into doing sports or, ‘You have to do this,’’ said Kip Spangler, a coach for the U.S. team who helps with Alpine skiers and strength and conditioning. “Lauren, she didn’t even know the U.S. ski team existed.”

“The weight of having a parent expecting you to do something is so much,” Lauren said. Not feeling such a weight, she added, is a competitive advantage.

From her bedroom window on the family home’s top floor, Sam can see Utah Olympic Park. That she would go on to train for a chance at the Olympics there was, she said, a happy accident.

“I want to tell people, ‘You don’t understand,’” Dan said. “It is a marvel to even get to this point.”