They batter bodies with rubber bullets and sear eyes with pepper spray. They lob tear gas and explosive flash-bangs at chanting crowds. They smash car windows. They shove people to the ground. They ram vehicles and point their guns.

Federal officers carrying out President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown in cities across the country have shot 13 people with guns. But far more often, they have used harsh tactics to scare or repel those they see as getting in their way. The officers, masked and kitted out with military-grade armor and rifles, have faced down peaceful protesters and people who have threatened, obstructed or attacked them, with methods that are less deadly than guns but still inflict grievous injuries. Hundreds have been hurt, and courts in at least four states have found that officers used force inappropriately and indiscriminately.

NBC News reviewed dozens of incidents since the spring and found that Department of Homeland Security officers have repeatedly deployed “less lethal” weapons in ways that appear to violate their own policies or general policing guidelines, unless they believed their lives were in danger. The review was based on interviews with lawyers, experts and protesters who were injured as well as witness statements, documents from criminal and civil cases and videos taken at protests.

The reporting reveals a cycle of escalation: Heavily armed immigration officers’ open-air raids motivated angry residents to meet officers head-on in the streets. Rather than trying to defuse a tense situation, officers abruptly used physical or chemical force. DHS seemed to apply these tactics with little discretion, whether protests were peaceful or violent, large or small.

“I’ve never seen federal agents so out of control and acting in such a malicious manner,” said Rubén Castillo, a former federal prosecutor and federal judge who now leads the Illinois Accountability Commission, a state effort to review allegations of abuse against immigration officers. “They said they were going after ‘the worst of the worst,’ then they became the problem.”

This conduct stoked public outrage, triggered backlash from local officials and prompted judges to intervene. For months, the Trump administration charged harder, fighting court orders and promoting an air of ruthlessness and impunity that signaled to officers they could use whatever means they saw fit. Government officials have defended officers’ actions as necessary and justified, while giving misleading or false accounts of some clashes.

The pervasive use of less lethal tactics, caught on video and ricocheting across social media, began in late spring and summer in California and Oregon, expanded into Chicago in the fall and reached a crescendo in Minneapolis, where officers shot and killed two protesters last month. Public outcry led the DHS to change on-the-ground leadership, end the surge in Minneapolis and order the wide-scale use of body cameras. “I learned that maybe we could use a little bit of a softer touch,” Trump told NBC News in early February, adding in the same breath, “but you still have to be tough.” On Friday, two senior DHS officials told NBC News that the agency has no immediate plans for more large-scale immigration operations focusing on specific cities. Still, the Trump administration says many newly hired officers have yet to be deployed.

DHS has blamed local politicians and activists for inciting violence, saying attacks on officers have climbed sharply, leaving them no option other than to respond in kind. The agency points to the conduct of some protesters, who follow officers with their cars, block them in the street, curse at their faces, blow ear-piercing whistles and clamor outside their hotels at night. At times protests have turned violent, with demonstrators throwing bottles, rocks and fireworks, and officers have arrested many people for allegedly trying to assault them or hit them with cars.

DHS said in a statement that its officers “are facing a coordinated campaign of violence against them.” The agency did not answer questions about specific instances of federal officers using less lethal force on protesters. Instead, it highlighted about two dozen alleged attacks on officers. In one, an officer suffered burns and a severe cut, requiring 13 stitches, while arresting a man from El Salvador; he was charged with assault and the case is pending. In another, a woman allegedly bit off part of an officer’s finger and was charged with assault; the case is pending and her lawyer said it was “meritless.” In a third, a Guatemalan national was sentenced to prison after pleading guilty to attempting to choke officers and grabbing one by the genitals.

“Despite these real dangers, our law enforcement shows incredible restraint and prudence in their exercise of force” to protect officers and others, the statement said. DHS said that claims of misconduct are “thoroughly investigated” and acted on “as necessary” but did not provide details.

Some who go to the street to protest or record officers’ conduct know that they risk getting badly hurt.

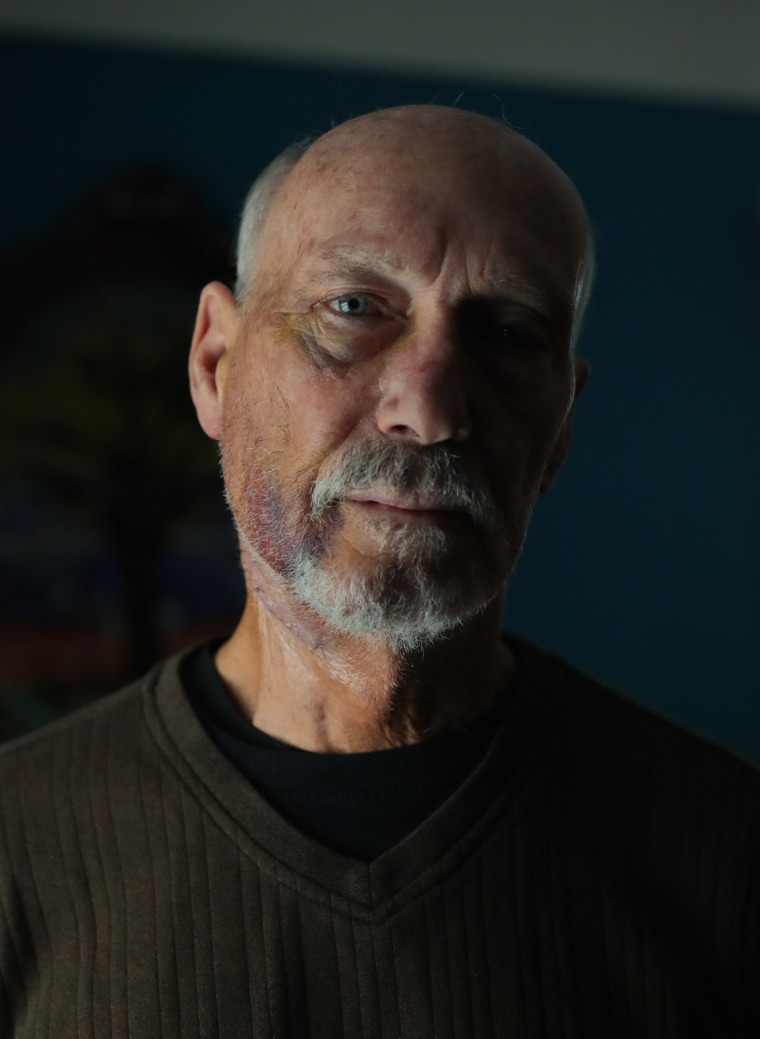

Leon Virden looked past the danger. He is 73, a lifelong Minneapolis resident who grew so upset after the Jan. 24 killing of Alex Pretti that he drove with his son to the scene. They ended up in a small group of chanting protesters in an alley where they came upon officers he believed were from DHS. One deployed a flash-bang grenade — which federal officers have used repeatedly at protests — and it exploded, shattering Virden’s face. Now he sits at home, popping Tylenol and trying not to aggravate his surgically reconstructed jaw.

“I’m really pissed off that these, you can call them anything you want, I call them agents of the Antichrist, that they can come in and do this and get away with it,” Virden said. “I’m pissed off. I hurt a bit, and I just want to see some change.”

Los Angeles: The campaign begins

The first immigration raids began in Southern California in late May, driven by Trump’s demand to detain 3,000 people a day. Masked and heavily armed federal officers, many of whom were accustomed to border patrols or targeted operations that did not typically involve tense encounters with the public, were now sweeping densely populated neighborhoods, scooping up Latino immigrants at bus stops, homeless shelters, Home Depot parking lots, farms, workplaces and homes.

The masked officers, in roving caravans of unmarked cars, drew resistance from angry crowds of immigration advocates and ordinary citizens, and were told by their leaders to meet anyone who harmed them with force.

“Arrest as many people that touch you as you want to. Those are the general orders all the way at the top,” the leader of the operation, Border Patrol commander Gregory Bovino, told agents in Los Angeles, remarks captured by a body camera and later filed in court. “Everybody f------- gets it if they touch you. You hear what I’m saying?”

Bovino said he planned to ship in “tractor-trailer loads” of less lethal weapons. He reminded agents that their actions would likely be caught on camera.

“Whose city is it, chief?” an agent said.

“F------ ours,” Bovino replied. “It’s our f------ city.”

The use of less lethal weapons — tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets and other projectiles shot from handheld launchers — is divisive, with some policing experts saying they risk ramping up violence and inflicting needless harm. Many local police departments began to rethink their approach to the weapons following violent confrontations with protesters over the 2020 police killing of George Floyd.

A new set of guidelines, published in 2022 by the policy group Police Executive Research Forum, said less lethal weapons should not be used against peaceful demonstrators — or against those engaged in “minor acts of civil disobedience” like blocking a street. Flash-bangs, developed for hostage rescues and designed to temporarily blind or stun, should not be used in demonstrations, PERF said.

DHS's policies don’t go that far, but they include some guardrails. The agency requires its divisions, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection, to train officers in de-escalation techniques and to use force only after a verbal warning, if possible, and a chance to comply. ICE’s use of force policy says less lethal force can only be used when no “reasonably effective, safe, and feasible alternative” exists and the level of force must be “objectively reasonable.” CBP’s policy is more explicit: It says pepper spray, pepper balls and chemical munitions can only be used on people who are actively resisting officers — and never on children, pregnant women or drivers, or at someone’s head, neck, groin or spine, unless an officer’s life is in danger.

Officers carrying out Trump’s campaign appear to have repeatedly crossed those lines.

Protesters and journalists covering the hostilities say officers shot them with pepper balls and hit them with tear gas canisters without warning while they chanted and shouted, took photos or were running away. Some were struck in the head or groin, sometimes at close range, and others suffered burns on their arms or legs, according to interviews and court findings.

Officers have been repeatedly filmed shooting pepper spray or powder directly into the faces of people who do not appear to be violent or threatening. Officers often shove protesters out of the way, sometimes knocking them to the ground. In some instances, children have been hit with tear gas. Two young men were partially blinded by rubber bullets in Los Angeles last month; a DHS spokesperson previously minimized one of the men’s injuries and said federal officers had been faced with a "mob" of rioters.

“It’s not every agent. But there is a large majority of them, maybe it’s the new hires or less experienced people, who are on edge, have this power trip, feel above everybody else, and they’re taking it to the extreme,” said Abigail Olmeda, 27, who said she was struck with rubber bullets, one of which hit her in the forehead, while holding a sign and shouting at federal officers during a June protest in Santa Ana, California. She said she experienced brain fog for months.

The rush to put thousands of immigration officers in the streets allowed less time to prepare them for the resistance they encountered, which made escalation — including the use of less lethal weapons — more likely, said Joseph Lestrange, a former head of public safety and border security for ICE’s investigative arm.

“You’re setting officers up for failure, to get hurt and to hurt the public,” Lestrange said.

In its statement, DHS said its officers are “held to the highest professional standard” and given months of training, including how to use “the minimum amount of force necessary to resolve dangerous situations” as well as de-escalation techniques.

DHS said every time an officer uses force it must be reported and reviewed, and that any claim of misconduct is investigated. But the agency did not respond to a request to share how many use of force reports have been filed in the past year, how many investigations of excessive force it has undertaken, and whether any officers were disciplined, fired or charged.

The agency said claims that the officers are not well trained are “shameful and laughable.”

Federal law makes it difficult to sue a federal officer, although people in several cities have announced their intention to try. Many more have submitted their accounts in civil rights lawsuits aimed at slowing the operations.

One of them is Alec Bertrand. On July 10, Bertrand, 30, woke up to messages about DHS arrests at a farm in Camarillo, California. He had seen immigrant communities emptied and silenced by raids and decided to act.

He drove toward the farm and joined protesters chanting and screaming in a roadway standoff with federal officers. Then someone who looked like a supervisor went down the line talking to the officers, Bertrand said. Their postures stiffened, and they adjusted their gas masks. Someone said, “They’re going to shoot.”

Bertrand, a musician and recording engineer, said he heard no warning when the officers opened fire from about 10 feet away. A rubber bullet hit him in the groin, then the shoulder and leg as he turned to run. He felt a heavy thud on his left hand and ducked behind a car. One of his fingers looked mangled. He thinks he was hit with something heavy, like a tear gas canister.

“It felt like a war zone where there’s only one side that has weapons,” Bertrand said. “The only weapon that we had was our speech, our voices.”

Surgeons repaired one of his fingers with a screw, but he still can’t properly move it — or play guitar. He had to find a new job. He started therapy — physical and psychological. He found a lawyer who filed papers announcing his intention to sue DHS, saying officers “illegally and unlawfully assaulted” him. DHS previously declined to comment on Bertrand’s allegations but said officers had been attacked that day by people who threw objects at them.

Bertrand also shared his story in a lawsuit against DHS in Los Angeles, where a federal judge tried to rein in officers, saying they had “unleashed crowd control weapons indiscriminately and with surprising savagery.” The Trump administration is fighting that order.

Vincent Hawkins, an emergency room nurse in Portland, Oregon, believes DHS’s summer operations were a prelude to the force they used later in other cities. In June, he was hit in the face with a tear gas canister while he shouted at federal officers through a megaphone. He said he suffered a concussion and still has hourslong stretches, including at work, when he has trouble keeping his balance.

“DHS as an agency was seeing how far they could push that envelope,” Hawkins, 56, said. “How much could they hurt people exercising their free speech rights in nonviolent ways? How much violence could they bring on those people to shut them up that the public would tolerate?”

Chicago: ‘You are unleashed’

The pain tore through Amanda Tovar with such ferocity, she thought she had been shot.

“It hit me! It hit me! It hit me!” Tovar’s voice, cracking with panic, says in a Facebook Live video of a Sept. 19 protest outside an immigrant processing center in Broadview, Illinois, where she said a canister of a chemical agent struck her chest.

“You’re OK, nothing’s bleeding,” a woman says, trying to reassure Tovar. “Look at my face.”

But Tovar couldn’t calm herself. Dozens of fully fatigued, armed officers had emerged from beyond a facility gate and were headed toward her and the other protesters, who had been shouting but were not violent, she said.

They lobbed flash-bang grenades, tear gas and pepper balls. “F--- yea!” one agent exclaimed, according to a federal court order citing body camera footage.

Two days later, Tovar, 39, a mother and special needs teacher, was in so much pain she went to the emergency room, where she was treated for “chest wall trauma” and acute back pain, according to discharge papers. She said she was told she was lucky to be alive because the canister struck right over her heart, which can cause internal bleeding.

That was a taste of “Operation Midway Blitz,” which launched in Chicago on Sept. 8 just after Trump posted on social media, “I love the smell of deportations in the morning. Chicago about to find out why it’s called the Department of WAR.” Several days into the chaotic operation, an ICE officer shot and killed Silverio Villegas Gonzalez, a father from Mexico.

Protesters flocked to Broadview, where dozens of arrested immigrants were processed daily. Officers on a rooftop were recorded launching less lethal munitions at the media and peaceful demonstrators. The Rev. David Black said in interviews he had just prayed aloud for the agents when a pepper ball hit him in the head. Levi Rolles, a frequent protester known as “Spicy Jesus” who was charged with obstructing and resisting and is set to appear in court next week, was shot so many times, his back was covered with raw, round welts.

On Oct. 1, Stephen Miller, the architect of Trump’s deportation policies, announced a new anti-crime task force of law enforcement agencies including ICE. Criminals “have no idea how ruthless we are,” he said.

“I see the guns and badges in this room. You are unleashed,” Miller said. “The handcuffs you’re carrying, they’re not on you anymore.”

Three days later, a CBP agent shot and injured Marimar Martinez, 30, a U.S. citizen; the agent who hit her bragged about his aim in text messages.

Allegations of abuse mounted. Some officers in Chicago “laughed and made jokes about tear gassing protesters,” a federal judge found based on body camera video. Neighborhood after neighborhood felt the impact: Residents hid in their homes, schools went on lockdown and children rushed indoors from recess.

On Oct. 24, Miller sent another public message: “To all ICE officers, you have federal immunity in the conduct of your duties,” he said on Fox News. “You have immunity to perform your duties and no one — no city official, no state official, no illegal alien, no leftist agitator or domestic insurrectionist — can prevent you from fulfilling your legal obligations and duties.”

The next day, more mayhem erupted. In Chicago’s Old Irving Park neighborhood on the Saturday before Halloween, officers arrested a man and triggered a chain of events that ended with them shoving a father in a yellow duck costume to the ground and breaking the ribs of a 67-year-old resident. Officers then fired tear gas, filling the air and sickening a 2-year-old girl and her mother who were playing in a nearby field. DHS later said officers were responding to “agitators” who posed a threat to law enforcement. Organizers canceled a costume parade.

Carlos Rodriguez, outside in his robe, was dumbfounded by this show of brute force. “The tear gas. That was the thing that was just absolutely outrageous,” Rodriguez said. The officers, he said, “were in no shape or form in danger of anything.”

A week later, Trump was asked on “60 Minutes” if he thought some of the immigration raids had gone too far.

“No,” he said. “I think they haven’t gone far enough.”

Not long afterward, in the town of Cicero, a family drove with their 1-year-old to Sam’s Club with their windows down. Officers were seen on video spraying an orange substance into their car, leaving their daughter’s eyes burning, the family said.

After reviewing hours of footage from protesters and body-worn cameras, U.S. District Judge Sara Ellis found a litany of civil rights violations by DHS officers that “shocks the conscience.”

She barred the use of chemical weapons unless officers’ safety was in peril and demanded DHS officers tone it down.

They didn’t. In suburban Evanston, officers deployed tear gas widely following a car crash with a civilian vehicle, prompting several schools to go on lockdown. An officer pointed his gun at protesters. Another officer was videotaped pinning a driver down and punching his head into the pavement.

“They’re just cranking up the outrageous attacks and the brutal violence with every passing day,” Evanston Mayor Daniel Biss said then. “It’s horrifying to imagine where that might go.”

Minneapolis: A reckoning over force

The crackdown only accelerated.

A surge into Minneapolis swelled in January to roughly 3,000 federal officers, dwarfing the scale in Chicago. They flooded the city, encountering resistance nearly everywhere they went and using force to push protesters back, according to interviews and a review of dozens of videos.

As in Chicago, a judge, presented with evidence of repeated force against peaceful protesters — including an older couple who said in a court filing that officers pulled guns on them while they sat in their car — ordered officers to stop; and DHS, as it did in Chicago, convinced a higher court to pause the order.

The clashes crescendoed with the fatal shooting of two 37-year-old U.S. citizens: An ICE officer shot Renee Good dead in her car, and less than three weeks later CBP agents tackled Alex Pretti to the ground before killing him.

Furious residents took to the streets.

Drew Harmon, an organizer with grassroots group 50501, was protesting Good’s death when he said an agent reached under his helmet to pepper spray him at close range.

“It feels like someone just lit a match on your eyelid and put out a match on your eyelid,” he said. “Does that sound like law enforcement to you or how law enforcement should be in our country?”

Hours after Pretti was shot dead while restrained and kneeling, Leon Virden and one of his sons joined a protest near the scene. Some chanted, “ICE go home.” No one was doing anything remotely threatening, Virden said. From a group of officers standing about 30 yards away, on the other side of a Dumpster, came a tear gas canister, which one of the group tried to kick away. Virden said he stepped forward to kick it farther, and a flash-bang soared toward him and exploded in his face.

Dazed and unable to hear well, Virden didn’t realize how badly he’d been wounded until he got to a hospital, where he got stitches in his cheek and his shattered jaw was rebuilt with metal plates and wired shut.

“I thought I knew what to expect,” Virden said. “And this was beyond anything that should have happened. It was just, it was ridiculous.”

In the days after Pretti’s killing, amid growing condemnation nationwide over the shootings, the Trump administration pulled Bovino and hundreds of officers out of Minneapolis. DHS signaled a shift to more targeted deportation operations, rather than the broad sweeps and public confrontations of the past nine months.

And yet, on Jan. 31, after demonstrators in Portland, Oregon, blocked the driveway of an immigration facility, federal officers fired tear gas at a crowd that included children.

“Owie, it burns,” a little girl in a pink butterfly sweater cried.

In response, U.S. District Judge Michael Simon ordered temporary limits on use of force in Portland, saying DHS’s culture is “to celebrate violent responses over fair and diplomatic ones.”

“Our nation,” he added, “is now at a crossroads.”