New legislation set to be introduced Thursday would ramp up oversight of residential treatment facilities that a Senate investigation accused of putting profits above the safety of foster youths and children with mental health issues.

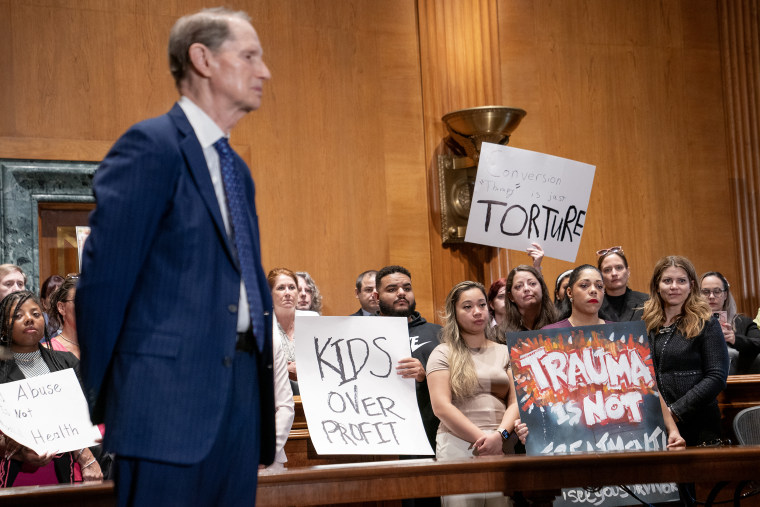

The bill, sponsored by Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., follows a broader national reckoning over allegations of abuse at facilities housing some of the most vulnerable children in society, which have been highlighted in recent years through congressional hearings, scores of lawsuits and investigative reporting.

“Young Americans who are struggling with their mental health or who are in foster care deserve far better than what they’re getting right now,” Wyden told NBC News in a statement, adding that the bill is intended to “give watchdogs the tools to spot and stop abuse quickly.”

The residential treatment facilities targeted by the legislation care for children with behavioral and mental health disorders, house foster youths and treat juveniles ordered into placement by judges. Many are operated by private companies but paid through Medicaid, by school districts and by private insurance, and they are largely inspected and licensed by state agencies.

Under the proposal, the Department of Health and Human Services would set up a national public dashboard to include how often children have been restrained or thrown in seclusion at the treatment centers, the facilities’ accreditation and licensure statuses, the rates they charge, their staffing levels and credentials, and results of recent inspections, among other data points.

Child welfare experts cautioned that the legislation would not cure all of the wide-ranging issues in the industry or the need for such intensive treatment. But some said the bill offered a good start to address gaps in the patchwork of state regulations.

“The bill highlights the scope of the issue,” said Jenny Pokempner, senior policy director at the Youth Law Center, a nonprofit organization advocating for children in foster and juvenile justice systems. “There’s so many aspects of this, and I think it is nice to have a bill that doesn’t purport to say if we do this one thing, it’s going to be fixed.”

Last year, the Senate Finance Committee released a report documenting how treatment centers operated by national corporations packed the facilities to capacity and failed to hire qualified staff members. Across 130 pages, citing internal documents and state inspection reports, it detailed examples of staff members’ injecting sedative drugs into children to keep them calm and facility employees’ dragging or throwing minors, along with graphic allegations of sexual assaults by staff members against children.

Before the Senate report emerged, NBC News investigations documented how facilities run by for-profit companies continued to contract with state agencies and school districts after inspections documented allegations of abuse and unsanitary conditions and lawsuits alleged that staff members injured children in their care.

The bill calls for increased standards for whom the facilities could hire, and it would create a student loan assistance program for people who work at facilities that rely on Medicaid funding.

Another provision in the bill would require states to investigate significant complaints against facilities within two days and, if they are substantiated, conduct larger examinations of the facilities and any others in a state that share ownership within 30 days. States often do not review facilities that share corporate ownership after one has a significant violation, an NBC News investigation found last year.

It would also close a loophole that allowed facilities in 21 states to bypass some licensing steps if they have accreditation by private organizations, such as the Joint Commission and the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities. Those organizations do not disclose details of their inspections of facilities they accredit or whether they have received complaints about the facilities. There have been several high-profile examples in recent years of children who died at treatment centers and programs that held accreditation.

However, Sarah Font, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis who studies child welfare systems, said there is a danger if lawmakers ultimately pass a bill that is too heavy on oversight and does not invest in getting more treatment providers certified in the most effective therapies.

“I worry a little bit that we’ve gone so negative in terms of how we think about residential care that we don’t acknowledge that it can be good for the kids who really need it when it’s done well, and we want really good people to be willing to provide that care,” Font said.

More government investigations would be launched if the bill became law. It would direct the Government Accountability Office to study and report to Congress on the companies’ marketing practices and order the HHS inspector general’s office to investigate how often states send children across their borders to be placed at one of the facilities.

A similar measure — the Stop Institutional Child Abuse Act, which cleared with bipartisan support late last year — called for a yearslong multiagency study of private treatment centers for youths that make up the so-called troubled teen industry.