MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Homes without indoor plumbing. Few streetlights. Virtually no public transportation. Half a century ago, residents of Boxtown, a neighborhood in South Memphis settled by formerly enslaved families, felt forgotten by the modern age. But no longer.

They are now at the center of a battle with the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, who built what his company xAI has dubbed the world’s largest supercomputer, Colossus, roughly 2 miles away.

City leaders see Musk’s arrival in Memphis, Tennessee, as a coronation of its future economy, a chance to transform the region into a “high-tech manufacturing hub.” Like their counterparts in Austin, Texas, and Atlanta, they were eager to recruit tech companies looking for homes outside Silicon Valley. Musk’s xAI would bring tax revenue and new jobs.

“It represents a tremendous opportunity,” Mayor Paul Young recently told NBC Nightly News, “an opportunity for us to take our economy to the next level.”

But in an area beset by industrial pollution, residents are wary of the methane gas turbines helping to power the electricity-hungry behemoth. The turbines give off nitrogen oxides, a key contributor to smog, and formaldehyde, among other pollutants, according to their manufacturer. Residents say public input has been limited and the company hasn’t been transparent about its plans.

xAI has vowed to stay below allowed limits on pollutants. In response to questions from NBC News, the company defended its process. “xAI works collaboratively with County and City officials, EPA personnel, and community leaders regarding all things that affect Memphis,” it said in a statement, adding that its tax revenue would support “vital programs and services” in the area.

Still, residents of Boxtown, a nearly all-Black community, have their doubts. “How do we really know what is coming from those facilities?” said Sarah Gladney, 71. “They can tell us anything, but how do we really know?”

Their skepticism has deep roots. For decades, outsiders with big plans have come and gone, sometimes leaving the air worse than they found it. But now the outsider also happens to be one of the country’s most powerful men, one who has been helping to run it alongside President Donald Trump. What happens next could test the limits of Musk’s power and the strength of environmental protections.

In at least two other states, Musk’s companies have run afoul of regulators and have been cited or fined for allegedly breaking environmental rules — Tesla in California, and SpaceX and The Boring Co. in Texas. The companies have denied wrongdoing.

Separately, Trump has vowed to shift the focus of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The agency has already dismantled teams created under the Biden White House to address environmental justice issues like those now facing Boxtown.

In coming weeks, the Shelby County Health Department is expected to decide whether to approve xAI’s permit to permanently install 15 turbines. Meanwhile, xAI has already purchased another property in nearby Whitehaven to expand its operations in Memphis.

Local residents aren’t backing down. Their distrust escalated into anger in late April, when they packed a meeting to fight xAI’s permit approval.

At the hearing, xAI senior manager Brent Mayo, clad in a black T-shirt and hat with the company logo, said its turbines would be equipped with technology to lower emissions, making it the “lowest-emitting facility in the country.”

After roughly a minute, several in the crowd began to chant, “People over property. People over property,” drowning him out.

The dirt roads, hogs and cotton fields that once made Boxtown feel more country than city are long gone. But the neighborhood still feels alive with history — both good and bad.

Older residents talk about how their ancestors settled here, building homes out of scraps of boxcars, which gave the area its name.

"They wanted something they could call their own," said Raymond C. Cheers, 74, a local historian, noting that some of the freedmen who lived in Boxtown are now buried in a cemetery there at Mount Pisgah Baptist Church.

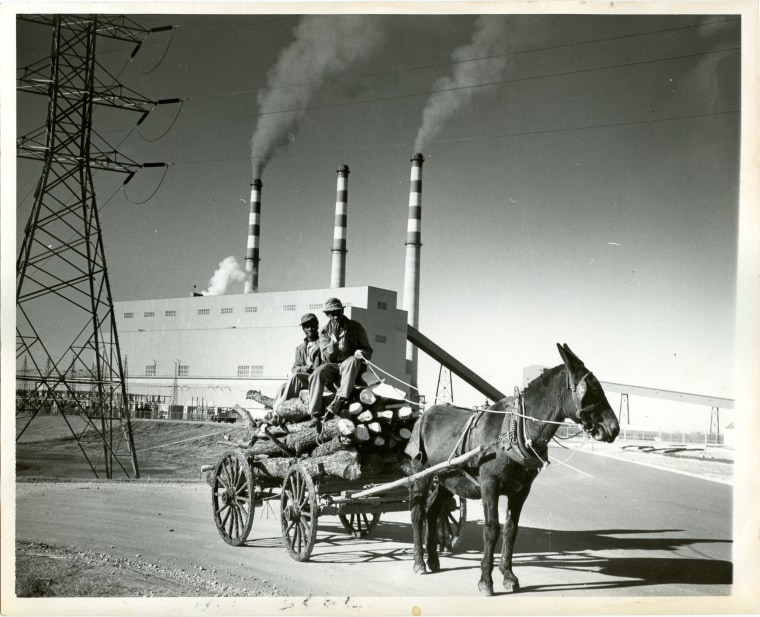

As a child growing up in the then-unincorporated Boxtown, Brenda Odell, now 76 and retired from a career in education, remembers going down with her family to check out the site of a future power plant.

It was the Jim Crow South, but Odell said there was a sense of hope around the Allen Fossil Plant. Yet, as she reached adulthood, many in the community still lacked electricity, even after Boxtown was annexed by Memphis. And by the time the Tennessee Valley Authority decommissioned the facility in 2018, millions of tons of hazardous coal ash were left behind.

“Everybody was excited, you know,” she said. “And now they’re having to take the coal away.”

Other businesses have come to South Memphis, leaving pollution in their wake. A facility that sterilized medical equipment closed shortly before xAI’s arrival, after the EPA found a heightened cancer risk in the area due to the plant's ethylene oxide emissions. Sterilization Services of Tennessee said at the time it had “never been out of compliance” with local, state and federal regulations and had issues relating to a lease extension before it closed.

KeShaun Pearson, president of Memphis Community Against Pollution, says the neighborhood, whose zip code has a median income just under $37,000, is sometimes seen as an easy target.

“They always come to southwest Memphis,” Pearson said. “They always come to what they believe is the path of least resistance.”

Shelby County, which includes Boxtown, leads the state in emergency room visits for asthma. One study found that Southwest Memphis has at least 22 local pollution sources and a cumulative cancer risk four times higher than the national average. Last month, the county received an “F” from the American Lung Association for its air quality.

Dr. Christie Michael, an associate professor with the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, who oversees a program for high-risk pediatric asthma patients at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital, said any additional pollution is too much.

“If we’re already struggling in Shelby County to meet the EPA standards, and we haven’t been,” she said, “regardless of how responsible this is, it’s not going to help.”

When xAI first launched its chatbot in 2023, it described Grok as an edgier AI, with a “bit of wit” and a “rebellious streak.” But training Grok to answer quickly and accurately requires massive computing power, roughly 200,000 graphics processing units housed in a facility whose main building is the size of 13 football fields.

By using a shuttered Electrolux factory, Musk was able to bring Colossus online in just 122 days and double its size in less than a year, giving his artificial intelligence company, xAI, a competitive advantage.

In a webinar, a consultant for xAI said the turbines the company used were intended to be temporary and did not need a permit for their first year of use, a view endorsed by the mayor, the health department and the Chamber of Commerce.

Environmental advocates disagree. “Not getting a permit from day one was circumvention,” said Amanda Garcia, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center. “And we’re certainly concerned that it’s going to continue.”

“xAI’s operations comply with all applicable laws,” the company said in a statement, adding that it intended to use “Lowest Achievable Emission Rate” turbines and relegate stationary turbines “to a backup power role, which will further reduce emissions” once another power source is available later this year.

Boxtown residents hoping to question Musk himself haven’t had a chance — he hasn’t appeared at any community meetings.

Sitting on her front porch with her friend Easter Knox, Gladney mulled over what she’d say to him. “What was the rush?” she said she’d ask.

“Did you even know that this community has already been fighting, and has all these polluters surrounding us?”

In its January application, xAI included a 19-page “environmental justice review,” arguing that the project was safe. The scope was limited to the nonresidential area closest to the facility, leaving out nearby communities like Boxtown.

Shaolei Ren, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of California, Riverside, who has studied the health costs of data centers, said emissions’ risks can be far reaching.

“A lot of people think if they are not living next to the emission sources, they are not affected by the air pollutant,” he said. “That’s not true because these air pollutants can really travel hundreds of miles, and they are not limited by the state lines or county lines.”

At the request of the mayor’s office, Chunrong Jia, a professor of environmental health at the University of Memphis, used xAI’s data to model the potential impact of running 15 turbines for Colossus, if approved, and projected its emissions were unlikely to threaten local air quality for residents. But Jia’s analysis was based on data provided by xAI rather than on independent air monitoring.

“The modeling results were preliminary,” Jia said. “We still had a lot of uncertainty, a huge uncertainty behind that modeling process.”

In an interview last week, Young said he planned to work with Jia to implement air monitoring in the coming months.

Days before the public hearing in April, some residents received anonymous mailers with the message: “Breathe Easy, Memphis!” equating xAI’s emissions to those of a neighborhood gas station.

But local residents remain skeptical. Toward the end of the hearing, Alexis Humphreys, a 27-year-old who lives in Boxtown, asked those in the room with asthma to raise their hands, as she held up her inhaler. Her mother and her 87-year-old grandmother have it too, she said.

“I can’t breathe at home, it smells like gas outside,” she said, about the existing pollution in the area, facing representatives of the Shelby County Health Department and Greater Memphis Chamber.

“How come I can’t breathe at home and y’all get to breathe at home?”

Though Boxtown has a legacy of environmental harm, it also has a tradition of activism.

Easter Knox moved to the area in 1977 after marrying her husband, Starry, and has come to be known to local children as “Mama Easter.”

Inside her home, she has a picture of Black men carrying the “I Am a Man” sign from the city’s 1968 sanitation strikes. Martin Luther King Jr. was in Memphis supporting the workers’ demands for safer working conditions when he was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel.

In Boxtown, Knox has seen echoes of the injustices he fought. In 2019, two companies announced plans to run a crude oil conduit, known as the Byhalia Pipeline, through the community, which activists saw as a threat to drinking water, though the companies denied it. Some families were sued in an effort to seize their land.

Knox and others protested the pipeline, and eventually, the oil and gas giants backed off.

She sees the battle with xAI as a similar one.

“It’s just sort of hard, you know, when people got money,” Knox said, wearing a mask because of her chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

She’s said she relies on her faith to stay positive and sees her activism as a gift to future generations.

“Hopefully when I’m gone and left the scene, they can continue to fight,” Knox said.

For now, xAI appears to be responding, at least to some extent. Through the Greater Memphis Chamber of Commerce, it announced plans to remove some of the turbines within two months.

And while the company recently acquired a 1-million-square-foot site in Whitehaven, the chamber said xAI would not be using gas turbines there.

Pearson will be watching closely. “Until we see all of the turbines removed from South Memphis, there’s nothing to celebrate, and there’s nothing to believe,” he said. “We believe facts down here.”

Gladney, a retired postal worker, has grown accustomed to living in a neighborhood that’s become a battleground in the fight for clean air.

Even before xAI moved in, she stopped walking as frequently in the neighborhood, which depending on the day, can smell like chemicals or sewage, she said.

“It’s really hard to continue to walk in a community where the unknown is going on,” Gladney said.

Still, she’s not willing to give up the fight. “Some people say, ‘Well, you know, why don’t y’all move?” she said. “And my question is, ‘Why don’t you move from where you live?’ If you keep moving, things will never change.”