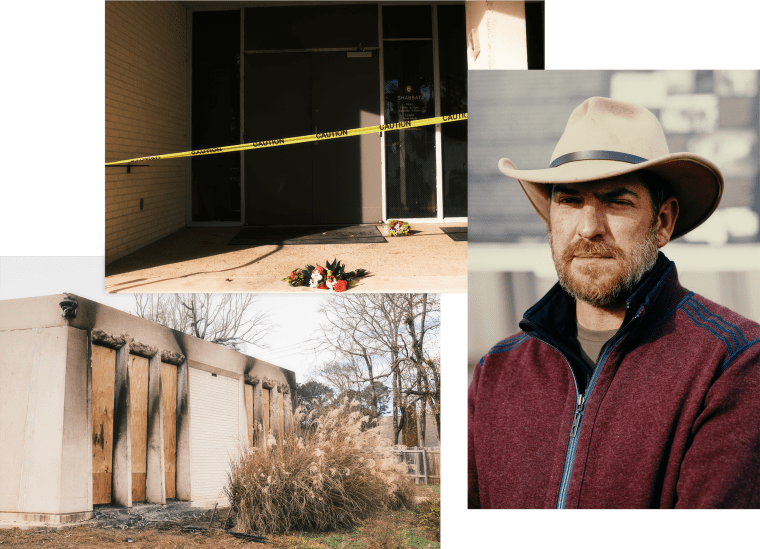

JACKSON, Miss. — The day after a fire ripped through Mississippi’s largest synagogue, Rachel Myers gathered a small group of children 5 miles away and showed them photos of the aftermath.

Myers, who teaches Hebrew school at Beth Israel Congregation, considered how to explain to elementary school-age children that the place where they sang and learned and prayed with their families had been attacked.

She brought images of the charred prayer books, she said, as a way to acknowledge: “We’re in this space that’s not our temple, because something bad happened at our temple.”

That “something bad” was arson, authorities said, gasoline-fueled flames set by a 19-year-old man who targeted the building’s “Jewish ties,” who referred to it as a “synagogue of Satan.”

One child said the ruins looked like a haunted house, Myers recounted.

Others had questions:

“Why would someone do something like this to us?”

Full answers will take much longer for the synagogue’s children, as well as its adults, to absorb, but for now Myers told them to focus on taking care of one another.

“I didn’t want them to be scared,” Myers said.

In a state where some Christian congregations are so large that churches use local law enforcement to help direct traffic, synagogues are scarcer sights. With 140 families as members, Beth Israel, founded in 1860, is an intimate yet vibrant hub for central Mississippi’s Jewish community.

Now, five decades after its oldest members survived a firebombing by the Ku Klux Klan, members are once again faced with an attack. Just hours before Saturday morning’s Shabbat service, flames and smoke licked through the synagogue, destroying at least two Torahs and many prayer books. The library where generations prepared for their bar and bat mitzvahs was ruined, as was an administrative office.

Federal officials charged Stephen Spencer Pittman, 19, with arson and said he admitted starting the fire. He suffered burns; no one else was hurt. Attorney General Pam Bondi condemned his alleged actions in a statement as a "disgusting act of anti-Semitic violence.”

Anti-Jewish hate crime incidents in the U.S. rose about 6% in 2024 compared with the previous year, according to the FBI’s most recent figures.

On Tuesday, state prosecutors charged Pittman with arson, as well, and said that if he's found guilty, he could be subject to a lengthier sentence under the state's hate crime law. His lawyer did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Zach Shemper, the president of Beth Israel, was still in bed when he got a call around 6:30 a.m. Saturday from the temple’s executive director telling him there had been a fire.

“I hung up immediately,” he said. “Nothing else was said.”

He rushed to the scene. The fire had started hours before, but he could still feel heat. His first thoughts were about what could be salvaged. Maybe the fire was an accident. A candle knocked over, perhaps.

“After I walked in and saw the extent of the damage and how hot the fire had to get, I realized there had to be some kind of accelerant,” Shemper said.

The library looked like a wasteland. Authorities said Pittman had used an ax to break into the building, and security video showed a man sprinkling gasoline across floors, couches, tables.

Shemper said he has had to suppress his anger to focus on moving ahead. The synagogue found a new location for an upcoming adult bat mitzvah. Local churches are offering space for services. The Mississippi Children’s Museum, where Myers works, hosted Sunday school. Shemper’s cousin drove up with a family Torah on loan from a neighboring synagogue, which in Mississippi means about 90 miles away in Hattiesburg. The congregation is raising money to rebuild.

As Shemper surveyed the damage, he saw that among the items spared was a Torah that survived the Holocaust. It was behind glass, which protected it from the flames.

“That was the first time that I had tears of joy,” Shemper said. “We’re all about remembering the past, and our historical relics mean a lot to us.”

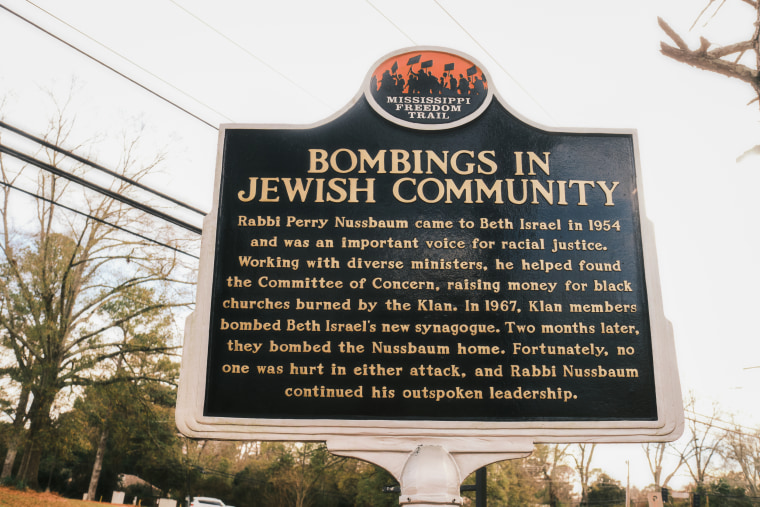

In Mississippi, the past looms large over Saturday’s arson.

“Destroying places of worship is absolutely nothing new,” said Frank Figgers, a civil rights activist who lives in Jackson.

Figgers noted that three civil rights workers who were murdered during the 1964 Freedom Summer — James Chaney, a Black Mississippian, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, two Jewish men from New York — had traveled to rural Mississippi to investigate a church burning.

Rabbi Perry Nussbaum, who was then the leader of Beth Israel, increasingly spoke out against racial injustice from the pulpit. In 1967, the KKK firebombed the building, destroying the rabbi’s office, and the group later firebombed his home. No one was hurt.

At one point, Nussbaum stayed at the home of Alvin Binder, a Jewish attorney in Jackson known for assisting the FBI in investigating the KKK, recalled Lisa Binder, 71, his daughter. She remembers her father keeping a gun under his desk for protection.

It was a scary time, but there are ways in which this moment is scarier, Binder said. Antisemitic ideas move through anonymous message boards and hard-to-trace platforms.

“What are we doing about that?” she said. “It’s almost more difficult to track down, or I would imagine it is. We knew who the heads of the KKK were at the time; it wasn’t like it was a secret.”

Myers, the second vice president of Beth Israel, said that even before she knew the fire was arson, she was determined to hold Hebrew school the next morning. She grabbed Hebrew books out of the burned building. She picked up a braided Havdalah candle so the children could start Sunday school as they always did, with prayers marking the end of Shabbat and the beginning of a new week. And she took pictures, thinking of the history that needed to be preserved.

Myers, who moved from Connecticut to Mississippi almost 20 years ago, has long worked with museums and educational institutions, including the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, which was also housed at Beth Israel and is now displaced.

While she was working at Mississippi’s history and civil rights museums, Myers taught about the 1967 KKK bombing. Now, she was looking into the faces of children and showing them pictures from that time. She asked, “What did they do next?”

One offered that Beth Israel still had a congregation: “We kept going.”

“‘OK,’ I said,” Myers recalled. “Well, what are we going to do next?”

The children imagined what they would want in the rebuilt space, Myers said. Colorful books. A cotton candy machine. A mural of past rabbis.

One young girl had another idea: “Just be more Jewish than ever.”