This article is part of “Pastors and Prey,” a series investigating sex abuse allegations in the Assemblies of God.

The policies sound simple: Mandatory reporting of suspected child abuse. Reference checks for all church staff and volunteers. Restrictions on who can use the title “pastor” to keep bad actors from operating under a cloak of authority.

These are child safety measures that the Assemblies of God, the largest Pentecostal denomination in the world, has chosen not to require in the United States. Denomination leaders in the U.S. urge congregations to adopt child protection policies, but say they cannot force all 13,000 of their churches to comply.

Halfway across the world in Australia, it’s a different story.

Amid a national reckoning over sex abuse a decade ago, Australia’s largest Assemblies of God organization voted unanimously in 2015 to require that all affiliated churches adopt child protection policies.

The safeguards that the U.S. denomination has rejected — saying they run counter to a religious structure grounded in local church autonomy — have now been implemented in Australia with the goal of keeping children safe.

Ryan Beaty, a former Assemblies of God minister in Texas and Missouri, said the reforms in Australia demonstrate that the U.S. church could impose child safety rules without running afoul of core theology.

“Could they do it? Yes, I absolutely think they could do it. Would they do it? That’s the real question in my mind,” said Beaty, a communications professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who studies religious institutions. “As of now, no Assemblies of God U.S. leaders are either willing or able to recognize that there is a problem that rises to the level of forcing a change.”

The approach in the U.S., where the global Assemblies of God movement was founded a century ago, has persisted despite decades of sexual abuse scandals and alleged cover-ups within the denomination’s churches and efforts by survivors to push for change. An NBC News investigation identified about 200 Assemblies of God pastors, employees and volunteers accused of sexual abuse in the last 50 years. Some accused pastors were rehabilitated and moved to other positions of authority, freeing them to abuse again, the investigation found.

“There’s just no oversight or accountability anywhere — it’s up to each leader how they want to address it,” said Jen Doyle, who says she was sexually abused by a worship leader in her Assemblies of God church in Pennsylvania in the late 1990s when she was 13. “The victims are the ones that are going to suffer the worst.”

‘Pastors and Prey’: NBC News investigates sex abuse in Assemblies of God churches

- Part 1: Assemblies of God church leaders allowed children’s pastor Joe Campbell to continue preaching for years after he was accused of sexually abusing girls.

- Part 2: An Assemblies of God college ministry glorified a sex offender and enabled him to keep harming students.

- Part 3: The world’s largest Pentecostal denomination shielded accused predators in a 50-year pattern of sex abuse, silence and cover-up.

- Part 4: Dozens of boys say they were abused in an Assemblies of God scouting program that vowed to raise godly men.

The General Council of the Assemblies of God, the U.S. denomination’s national governing body, responded to NBC News’ reporting by stressing its commitment to child protection, including “stringent standards” and voluntary training that it recommends to all churches, along with background checks it requires for all credentialed pastors. The denomination’s leaders argued that local church autonomy means instituting national standards is “impossible.”

When asked about Australia’s approach, the General Council said the Assemblies of God’s national church organizations around the world operate independently and sometimes adopt different rules and governing structures.

Sex abuse cases have also surfaced in Assemblies of God churches in England, Nicaragua, Argentina and other countries; the church has nearly 90 million members worldwide. Nowhere, however, has the issue prompted as big of a national outcry — and an urgent call for action — as it did in Australia.

The Assemblies of God took root in Australia nearly a century ago, and denomination leaders there also considered the autonomy of each church to be sacrosanct.

Then came the backlash.

Australian Christian Churches — the country’s largest Assemblies of God’s organization with more than 1,100 churches and 400,000 parishioners — was subject to an unprecedented national investigation into child sex abuse, prompted by mounting reports and allegations of cover-ups.

Australia’s Royal Commission, a government-appointed panel with broad investigative authority, led the inquiry, driven by the mishandling of child sex abuse in the Catholic Church. Its sweeping investigation, which was unveiled in 2012, expanded to cover other religious and secular institutions, including the Assemblies of God.

The commission took evidence from 1,200 witnesses from 2013 to 2017, and aimed to determine the nature and cause of abuse and who should be held accountable. And while it could not dictate policy changes, it could force leaders into the national spotlight to explain what went wrong — and how they planned to fix it.

Sen. David Shoebridge, an Australian legislator who was among those who called for the commission’s creation, described it as an emergency measure.

“The church was well aware of credible allegations of child sexual abuse — and yet instead of protecting survivors and potentially future victims, acted to protect the reputation of the church,” Shoebridge said of Australian Christian Churches, pointing to church records and testimony. “It is a deep, deep betrayal of not just Christian values, but I think basic human values.”

One case caused an instant furor.

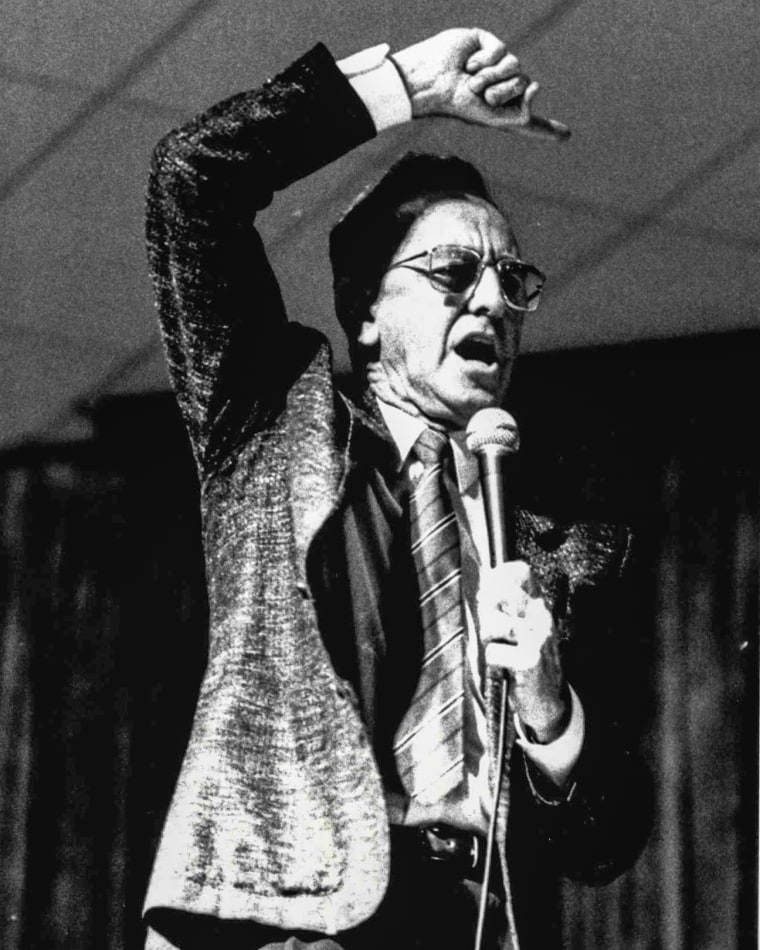

The commission determined that a leading Assemblies of God pastor in Australia, Frank Houston, had sexually abused a 7-year-old boy decades earlier, and that when church leaders found out, they didn’t report it to police. Instead, the leaders — including Houston’s son, Brian Houston, the founder of the global megachurch Hillsong — allowed the pastor to quietly retire.

For many within the Assemblies of God, it was the first time they’d heard allegations that Frank Houston had committed crimes against children — and that his son, who was then president of the church’s national organization, had failed to go to the authorities. (Brian Houston was later acquitted of a charge of criminally concealing his father’s sex crimes after he said the victim in the case had asked him not to report it.)

“We were gutted. We were gutted like a fish,” said Bob Cotton, a former Assemblies of God pastor who leads a church in Maitland, Australia.

The Royal Commission concluded in 2015 that the Assemblies of God had mishandled the Houston case and others like it. The commission faulted the denomination for failing to adopt necessary safety measures to prevent and respond to abuse — and for ultimately giving “priority to the protection of pastors over the safety of children.”

The commission singled out the church’s decentralized structure.

“Perhaps the most significant factor that affected institutional responses to allegations of child sexual abuse was the autonomous nature of Pentecostal churches, which meant that senior pastors had discretion about whether to adopt child protection policies, including in relation to the training, supervision and discipline of staff,” the commission said in its final report.

In their defense, top church officials had argued during public hearings that the Australian Christian Churches was fundamentally a “fellowship of autonomous independent churches,” and that the national organization had no authority to require individual churches to follow specific policies — the same defense used by leaders in the U.S.

But the prominence and power of Australia’s Royal Commission put enormous pressure on Australian Christian Churches, among other denominations, to make internal reforms.

In 2017, the leaders of Australian Christian Churches returned to testify before the commission. This time, they acknowledged the shortcomings of the denomination’s child protection policies — and described a big change.

“We did a lot of soul searching,” pastor Wayne Alcorn, the denomination’s national president at the time, told the Royal Commission. “We realized that many things that we were asking of our churches were recommended. Now they are no longer recommended — they are required. And, really, that was the primary thing.”

In a statement, the Australian Christian Churches said it is “committed to ensuring all aspects of church ministry to be safe.”

The group still considers itself to be a “voluntary cooperation” of self-governing churches. At the same time, all affiliated churches must adopt its minimum child protection policies, including requirements to report suspected abuse and for all staff members and volunteers to undergo reference checks. The group’s new national office and state offices for church safety oversees these policies.

“The way we’ve written the ACC policy is to say, ‘Here’s what you will need to adhere to,’” said Peter Barnett, director of Creating Safer Communities, an independent child protection organization that Australian Christian Churches hired to help draft and implement the changes, and that now operates the group’s hotline for reporting safety concerns. “Each local church has to actually sign off that they will do that.”

The denomination also now requires “anyone referred to as a Pastor” to be credentialed by Australian Christian Churches, a process requiring criminal background and reference checks. In the U.S., each Assemblies of God church’s senior pastor must be similarly vetted and credentialed, but youth pastors, worship leaders and other associate ministers are not required to receive the same level of scrutiny from the national organization.

Many Australian survivors and advocates believe that the changes don’t go far enough.

Critics point out that there is little way to know if churches are actually following the rules. Australian Christian Churches doesn’t have a formal audit process; the denomination didn’t respond to questions about whether any noncompliant pastors or churches had been expelled.

“The mice are still in charge of the cheese,” said Cotton, the former Assemblies of God pastor, who left the denomination over its mishandling of child sexual abuse.

And just like in the U.S., some abuse survivors in Australia say they feel betrayed by church leaders who have fought efforts to seek accountability and compensation.

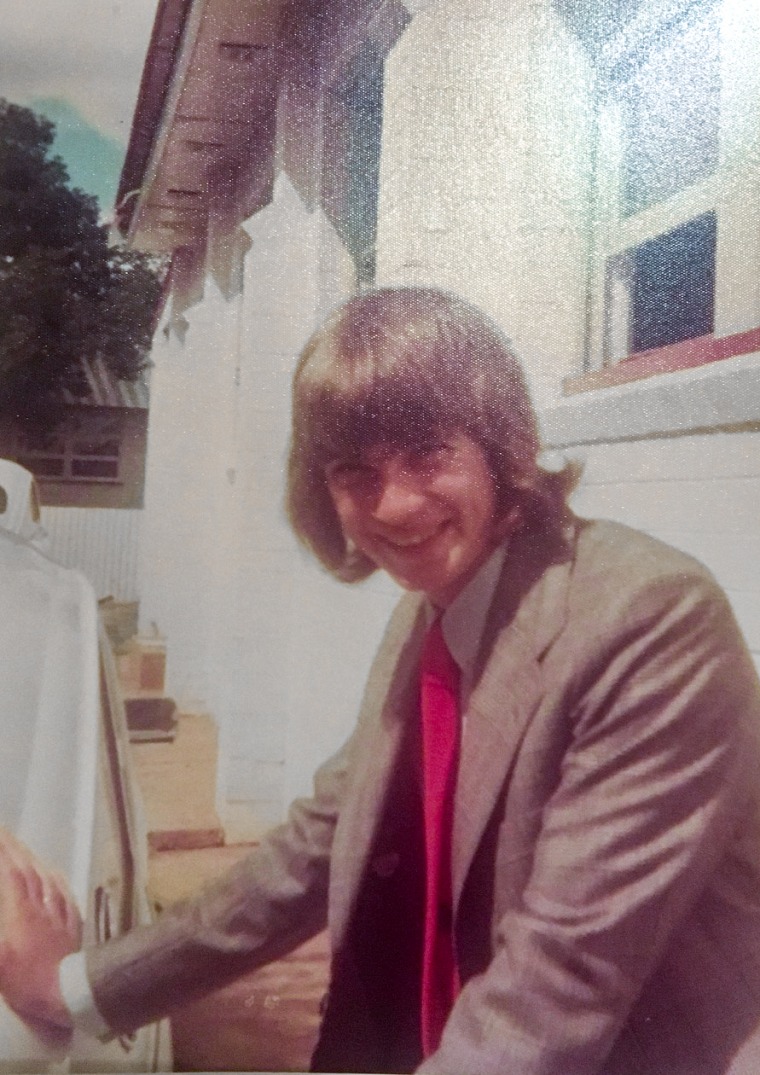

Peter Townsend, who was sexually abused in the 1970s by an Assemblies of God youth pastor and Royal Rangers scouting leader when he was about 12, helped send his abuser to prison in 2017. But when he sued Australian Christian Churches two years later, the denomination denied it was liable, arguing that it had no control over its member churches when the abuse occurred.

“They pushed me under the bus and watched the bus run over me,” said Townsend, whose lawsuit was unsuccessful.

Still, the Australian denomination has done more than U.S. Assemblies of God leaders have been willing to do.

In 2019 and 2021, the General Council of the Assemblies of God in the U.S. considered a similar proposal to require churches to adopt child safety policies. But when it came time to vote, church leaders objected.

The measure would play “right into the hands of plaintiffs’ attorneys” and expose the church to greater liability if victims sued, General Secretary Donna Barrett said in 2021. The General Council declined to adopt the measure.

Beaty, the former Assemblies of God minister, said the decision reflected an unspoken belief among senior church leaders: that the institution’s well-being comes before all else.

“If the Assemblies of God falters, people go to hell,” Beaty said. “That’s what they believe. And they will sacrifice some members to protect that mission.”