Nuclear fusion as a future abundant energy source, and a key tool to combat global warning, could get a major boost next week if Group of Eight leaders agree to a site for the world’s first fusion test reactor.

Group of Eight members France and Japan have been competing for the right to build a fusion reactor — a project called ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) and expected to cost $12 billion over 20 years.

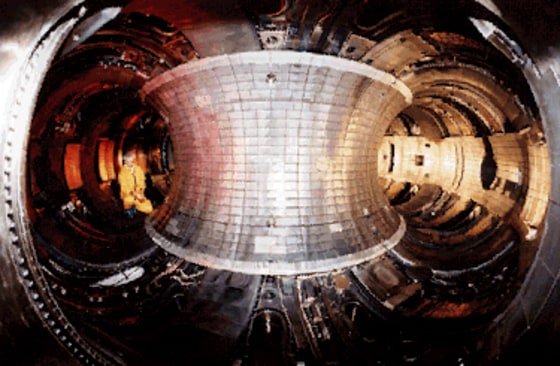

Nuclear fusion mimics the way the sun produces energy and could potentially provide a nearly inexhaustible supply of low-cost, clean and non-radioactive energy using seawater as fuel.

Global warming, a problem experts say could be eliminated if nuclear fusion becomes the favored energy source, is on the agenda at the July 6-8 summit of rich nations in Scotland —meaning the ITER project could be up for discussion too.

Nuclear power does not emit carbon dioxide, a key greenhouse gas that many scientists fear is behind global warming, because it does not burn fossil fuel.

Nations see potential, need

“ITER will be decided ... I suspect it will be at the G8 meeting in Scotland,” said Robert Aymar, director-general of the Swiss-based European Organization for Nuclear Research.

ITER — also Latin for “the way” — is backed by the United States, the European Union, China, Russia, Japan and South Korea with India and Brazil expected to join soon, Aymar said.

“These countries at the political level have realized that there is a potential and there is a need and they are trying to make this effort,” he said.

The fusion reactor project had been ready for launch already in 2003 but the U.S.-led war in Iraq got in the way of a decision on location, Aymar said.

U.S. President Bush then wanted to reward Japan for its support on Iraq, leading to a tug-of-war with the European Union over where the site would be built.

EU officials have said they believe Cadarache in the south of France will be the site of ITER.

Fission vs. fusion

Aymar and Carlo Rubbia, an Italian nuclear scientist who shared the 1984 Nobel physics prize, spoke to Reuters on the sidelines of an energy symposium organized by the Nobel prize foundation.

Nuclear and solar power look like the only viable solutions for the world’s growing energy needs without exacerbating global warming, Rubbia said, adding that a quarter of earth’s population — 1.6 billion people — have no electricity.

He said conventional nuclear power, obtained through fission instead of fusion, would eventually disappear.

Conventional nuclear reactors — in which uranium atoms are split, creating hazardous radioactive waste such as plutonium that can be used in nuclear weapons — currently produce around 15 percent of the world’s electricity.

Fusion reactors would “remove some of the great concern that we had in the past” such as the Chernobyl disaster, Rubbia said.

Scientists have not yet mastered the fusion process but are “confident that the goal will be achieved,” Aymar said, adding that a commercial fusion reactor would probably not come on stream until around 2050.