Astronomer Michael M. Davis checked his computer. One of the antennas on the state-of-the-art radio telescope being built in the valley outside his office was picking up an unusual pulse from beyond the earth. A signal from another intelligent civilization? Not today. It was the Rosetta Satellite, en route to study a comet.

Hopeful moments followed by disappointments like this are par for the course for researchers at the SETI Institute, the privately funded successor to the now defunct government project dedicated to searching for alien life. They have been searching the heavens for decades, but they have not been able to gather enough data to conclude, or even guess, whether we are alone in the universe.

Hunting with new tools

This time, however, the scientists hope things might be different. This month, the first telescope designed specifically for such a search began scanning the skies. It is still in its early stage of development, but when it is completed the telescope will be so powerful that it will be able to look at more stars in a year or two than we have in the past 45 years.

"The absence of a signal so far is not particularly compelling," said Davis, an adjunct professor emeritus at Cornell University who recently joined SETI to oversee the telescope project. "We could have a billion intelligent cultures with radio waves buzzing around them . . ., but we haven't had the capability to detect them."

Denounced a decade ago as a misguided effort to find "little green men" and cut off from government funding, SETI, which stands for search for extra-terrestrial intelligence, has found a new following among Silicon Valley titans and techies elsewhere who are interested in space. They have infused the institute with money and unconventional technical ideas, bringing a new respect and energy to the organization. Some argue that being cast away by the federal government was the best thing that could have happened to SETI, that it has become stronger and more innovative in the private sector than it ever could have as part of a public bureaucracy.

Its scientists now regularly publish in some of astronomy's most prestigious journals and the National Science Foundation recently announced it would be eligible for grants once again. Its financiers represent the founders of some of the world's top technology companies: Microsoft Corp.'s Paul Allen, Intel Corp.'s Gordon Moore and Cisco Systems Inc.'s Sandy Lerner. Sun Microsystems Inc. has donated top-of-the-line computer servers and other equipment to SETI projects, and current and former executives of Hewlett-Packard Co. have provided their expertise.

Challenge of a lifetime

The high-tech industry has always been a place for dreamers, people who believe in the power of science to solve any problem. Building the ultimate alien-search machine is the challenge of a lifetime for many techies, most of whom spent their childhoods immersed in "Star Wars" and "Star Trek" and reading comic books about extraterrestrial superheroes.

"To use hardware and software to find the meaning of life, it's interesting to them philosophically and technically," said Seth Shostak, a California Institute of Technology-trained senior astronomer at SETI, which is based in Mountain View, Calif., in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Allen said in an interview that when he was young he would go every week to the library with his mother and pick up a stack of science fiction books that would make him dream of "crazy ideas." Allen, who has helped fund the Experience Science Fiction Museum in Seattle and SpaceShipOne, the first privately financed manned spacecraft, said it was man's first walk on the moon in 1969 that made him believe that technology could turn his ideas into reality.

"The sheer knowledge that another civilization exists — that would be an amazing thing," Allen said.

Playing the odds — on a budget

Backers hardly regard their project as some frivolous exercise. Alan Bagley, who spent nearly 40 years as an engineer at Hewlett-Packard Co. and was most recently the head of the company's frequency and time division, said he joined SETI's board because "the real long shot is that there's no one else out there." Mathematician Linda Bernardi, chief executive and president of ConnecTerra Inc. got involved because SETI is about "what is possible." "The odds that we are the only life in existence seems very unreal," she said.

The design for the new telescope arose from series of marathon brainstorming sessions between the institute's astronomers, University of California at Berkeley scientists and some of the tech industry's most respected big thinkers.

Most powerful radio telescopes rely on one giant antenna, the power of which increases with the diameter of it dish. Hewlett-Packard's former head of research and development Bernard M. Oliver, who passed away in 1995, imagined building a telescope which he called a "Cyclops," or a giant eye made from an array of smaller antennas. At the time he came up with the idea several decades ago, hooking all those antennas up to computers would have been enormously expensive. But with the price of electronics falling rapidly over the past few years, that is no longer an issue.

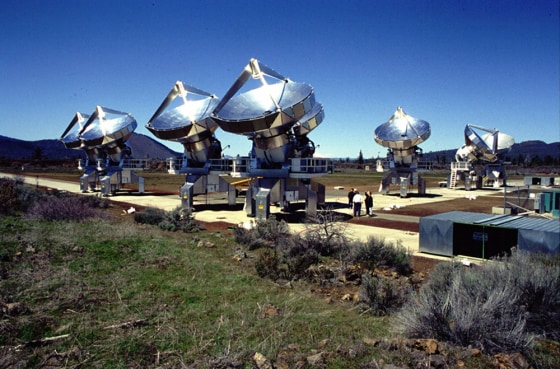

The Allen Telescope Array, named after its most generous donor, Paul Allen, will be made up of 350 or more small silver aluminum dishes that will be spread out over 90 acres in a randomized pattern. It is being built in the northern tip of California in the most other worldly of landscapes — a field filled with desert bushes and lava patches and surrounded on all sides by snow-capped mountains.

Many of the components used in the new telescope are basic off-the-shelf parts, making it significantly cheaper and easier to build than its counterparts. While a large telescope might cost $200 million to build, Davis said, the SETI one will cost about $35 million and will by some measures be even more powerful and sophisticated.

"This thing ultimately is made up of 350 souped-up backyard antennas," Shostak said. About a dozen of the antenna dishes are operational now. By the end of the summer, the number is expected to grow to 30. By the end of the year, to 42. The array is expected to be completed sometime in 2008.

Interstellar waiting game

Glamorized in the movie "Contact," which starred Jodi Foster, and other Hollywood movies as fast-paced and exciting, the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence is in reality a lesson in patience.

SETI astronomers begin with lists of planets ranked by how hospitable they may be to life as we know it. A number of criteria are factored in, such as their age, how close they may be to sun-like stars, whether they have the potential to hold liquid water.

The astronomers then go to each of these "hab stars," or habitable environment stars, one by one and scan them for any transmissions across all frequencies.

Until the Allen Telescope Array began operating, the search for alien life was conducted on a part-time basis. The scientists would usually borrow time on other telescopes, record the data and then analyze it for months afterwards using computer systems. If some out-of-the-ordinary signals were detected astronomers often had to wait for another turn to gather more data, a time-consuming process.

Now SETI can scan places 24 hours a day, seven days a week and run the analysis in real time.

Since the spring of 1960, when a then-young astronomer named Francis Drake first pointed a telescope at some nearby stars and listened for extraterrestrial signals, SETI scientists have thoroughly analyzed 1,000 stars. Over the next two decades, the Allen Telescope Array hopes to be able to study 1 million more. But with an estimated hundred billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy and a hundred billion galaxies in the universe, to say there's a lot more work to be done is an understatement.

On a recent morning a few hours after dawn, Davis walked briskly around the high-desert field, checking to make sure the saucer-shaped antenna dishes were being installed correctly. He then returned to his office to sit in front of a computer and coordinate with his colleagues in SETI's Silicon Valley office to remotely point the telescope every which direction and began the task of trying to differentiate between manmade phenomena and possible alien ones.

And so it will go for the next year, decade, century, millennium or longer. Davis knows that even if other civilization exists somewhere out there, the chances of finding it in his lifetime are remote. "If after a thousand years we can't confirm a signal, it certainly says something." Davis paused, frowning. "Maybe they are quieter than we are. Or maybe they aren't there at all."