Starbucks Corp. is taking longer than expected to introduce music CD burners to its coffee outlets because of design challenges and the high stakes of putting Starbucks' cafes into the music business.

Starbucks was hot on its new music service back in March, announcing it would install CD burners in 2,500 stores within two years, allowing customers to create their own CDs. Seattle stores were slated to get the service in April. Then it was August.

Now the program is more modestly being described as a test. After a six-month delay, 10 Seattle stores will begin offering the music service this fall, followed by a similar test-marketing effort in Austin, Texas. No other openings are ready for announcement.

Don MacCannon, Starbucks vice president of music and entertainment, said managers have grappled with the design challenges of presenting CD burners in Starbucks coffeehouses in a way that's eye-catching and accessible without intruding on the cafes' ambiance.

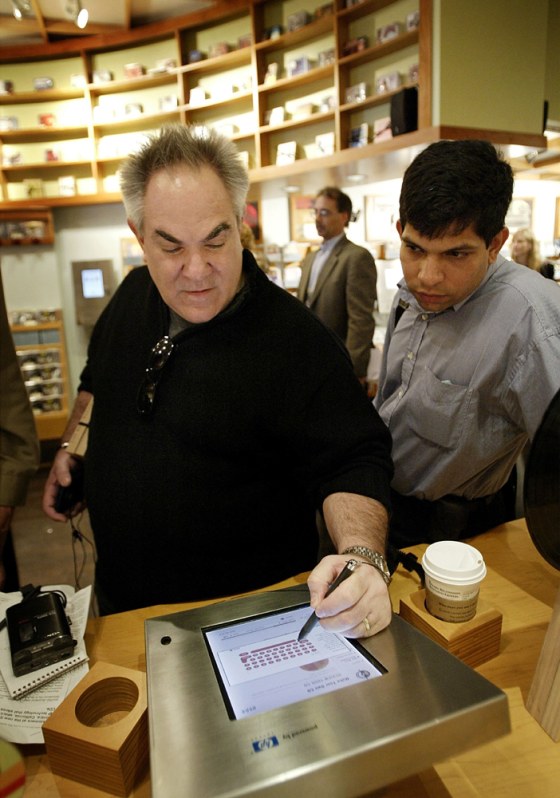

Now, the machines are designed and in production, MacCannon said. And Seattle residents should finally be able to take home a CD with their latte within a month or so, he said.

The company's initial enthusiasm stemmed from the positive customer response to the prototype Hear Music coffeehouse that Starbucks opened in Santa Monica, Calif., in March. The popular store is packed with more than 60 listening stations where customers can browse music archives, burn CDs, design their own packaging and take home a finished product.

"When we opened Santa Monica, the idea was to take the technology and very quickly get it into Starbucks stores," said MacCannon, a founder of Hear Music who sold the company to Starbucks five years ago. "But we wanted it integrated into the cafe without taking over the cafe. We decided we wanted the best solution, which took longer to design, manufacture and deliver."

The company isn't revealing what the machines will look like or even how many will be in each Starbucks store. MacCannon jokes there will be "more than one, less than 70." The challenge is to offer enough machines that customers can usually find one available, without blocking the latte line or knocking out the room needed for chairs.

The slow progress of the music service may be a byproduct of how important an initiative the CD-burners are for Starbucks. It's essentially the capstone of a series of music-related concepts Starbucks has introduced, MacCannon said.

There's been the exclusive-content CDs — such as the compilation by the late Ray Charles, released this week — the introduction of store-based wireless high-speed Internet, or Wi-Fi, and most recently the company's own satellite radio channel.

With the addition of 10,000 searchable CD titles in a virtual inventory that customers can pick and choose tracks from, complete with reviews and advice, MacCannon said Starbucks hopes to change not just what customers expect from coffeehouses, but to change the music industry itself.

This may tip the balance from Starbucks being thought of as a coffeehouse where you might hear good music to being considered a music store that offers good coffee. Now that a music store can be compressed to the size of a small kiosk, the very idea of a music store is about to change, MacCannon said.

"This technology makes it about who has the most customers coming there the most frequently," he said. "That's where we think Starbucks can play a transformative role in the music business. We're one of the most frequented stores in America."

Analysts have been enthusiastic about what the new music service could add to Starbucks' corporate performance.

When the March announcement was made, Smith Barney restaurant analyst Mark Kalinowski wrote, "We calculate that if Starbucks can get 5 percent of its customers to spend $10 on music annually, it would add one to two full percentage points to overall revenues."

But some observers are skeptical about how Starbucks customers will take to the CD-burning idea. The pricing Starbucks has planned is well above that being offered by some Internet music-downloading services.

Seattle-based RealNetworks Inc. recently announced a 49-cents-per-song download sale, for instance. By contrast, MacCannon said Starbucks plans to charge about $12 for a 10-song CD with liner notes and packaging.

One follower of the music service's progress is Dow Lucurell, owner of one of Seattle's largest independent coffeehouse chains, Uptown Espresso. With many young people routinely downloading music off the Internet, it's unclear if customers will pay much more for a better-looking product, he said.

"It's a really difficult market to compete in, with the prices coming down," he said.

But if CD burners are a hit with customers, Lucurell thinks Starbucks may be onto a program that would set it apart from other coffeehouse competitors. Because of the cost of the technology involved, it's unlikely many smaller chains will follow Starbucks' lead and install CD-burning units of their own, as they did with Wi-Fi, Lucurell said. Uptown Espresso won't be installing them, he said.

For Starbucks, offering customized music broadens the company's retail offerings. And there's lots of ways Starbucks could promote the service to customers, Lucurell points out -- Starbucks VISA rewards could now be paid in music tracks, or the company could offer a bonus track with each Starbucks card purchased, for instance.

Starbucks isn't the only one thinking there's a possible convergence between coffeehouses and downloadable music. The troubled Musicland chain said in late August that the company plans to make over its 900 stores to have "more lounge-like atmospheres, in an effort to increase online music sales."