The collapse of East Asia’s economies in 1997, or the rescue of Mexico’s in 1995? The bloody humiliation suffered by U.S. troops in Somalia, or their casualty-free victory over Yugoslavia’s armed forces in Kosovo? These are just a few of the significant foreign events that took place on Bill Clinton’s watch. How credit and blame is apportioned largely will shape history’s view of Clinton’s eight years at the helm of American foreign policy.

The idea of passing judgment on a president’s global legacy is daunting even years after an administration’s tenure has ended. To do so immediately afterward is risky, and even more so during a decade like the 1990s, when the international certainties that had governed foreign policy during the Cold War disappeared.

Clinton will be judged, rightly or wrongly, for the outcome of many of the events that took place during his watch. The question is: Which events will be remembered? Will it be his successful agitation for peace in Northern Ireland or the collapse of his efforts in the Middle East? Will his tardy but ultimately decisive intervention in Bosnia be his legacy, or the inaction of his administration when Rwanda’s Hutu’s began hacking some 750,000 Tutsis to death.

The Cold War's legacy

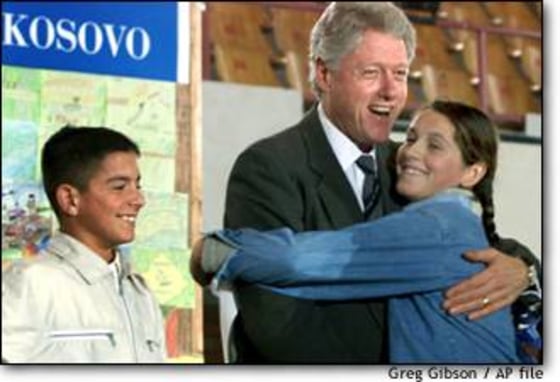

In Central and Eastern Europe, Clinton is cheered as the president who called Russia’s bluff and brought much of the region under NATO’s protective umbrella. He also is viewed, along with Madeleine Albright, as the one who stood up to Yugoslavia’s Slobodan Milosevic and contained Belgrade’s play for a “greater Serbia.”

Yet in Russia itself, the most important of the region’s countries, Clinton backed the faltering Boris Yeltsin long after his pledges to reform the economy could be taken seriously. Will some future cataclysm in Russia be viewed, in retrospect, as the result of the Clinton team’s tolerance of Yeltsin’s backsliding?

Russia’s fate is probably out of the hands of any American president - and perhaps any Russian one, too. But it appears likely that the carte blanche afforded Yeltsin and the crony-capitalism his government fostered will be viewed as a failing of the Clinton years.

On the other hand, despite desperate poverty and the humiliation of going from superpower to economic basket case, Russia remains, for now, quasi-democratic and poses no overt threat to the United States. While Yeltsin’s successor, Vladimir Putin, may not be completely to Washington’s liking, there has been no rise of a nationalist dictatorship, nor a restoration of Soviet communism, as many pessimists had predicted. As with many other issues - from the Middle East talks to Clinton’s infusion of military aid to Colombia - the verdict on his Russia policies is out.

The bigger picture

By concentrating on individual successes or failures, many pundits and editorial writers are now seeking to paint a picture that suits their tastes: from Clinton the Great Conciliator (in Belfast) to Clinton the Appeaser (in North Korea).

A more sober assessment needs to consider not only the events of Clinton’s tenure and his reactions to them, but also his administration’s struggles to divine a plan for exploring the virgin territory of the post-Cold War world. What does Clinton bequeath his successor regarding the proliferation of missiles and nuclear weaponry? What new perspective has been cast on the proper role of military force in pursuing U.S. interests? What about the United Nations? Global warming? International terrorism?

Put more simply, did the Clinton years rebuild a consensus for American foreign policy, or did his administration act as a fire department, enforcing existing codes, urging safeguards and rushing out to battle blazes without a larger purpose?

Unfinished business

The to-and-fro of events since 1993 suggests the Clinton team acted more like the latter. Indeed, the kindest appraisals of his performance have tended to stress that the United States — and the wider world as well — is living through an uncertain, transitional period. The Cold War is over, and the era that will follow has not quite begun. America, while disproportionately influential, confronts a vacuum overseas and an era in which financial markets and stateless zealots pose more of a threat than traditional military forces or alliances. In such an atmosphere, many critics of the Clinton administration have taken the president and his foreign policy advisers to task for spending time and political capital on what they consider relatively small issues — Haiti, Northern Ireland, East Timor — rather than the emerging relationship with China, reforming the former Soviet states or redefining relations with NATO and Japan.

Clinton’s harshest critics believe the administration has squandered a unique period in history and failed to take advantage of extraordinary opportunities that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and the global proxy wars of the Cold War. George W. Bush’s national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, said such “periods of transition are important, because they offer strategic opportunities. During these fluid times, one can affect the shape of the world to come.”

The use of force

Further, Rice and others accuse Clinton’s administration of running down the military by paring defense spending and living off the fat of the Reagan defense buildups of the 1980s, while sending American troops off to an unprecedented range of new overseas missions. From the administration’s earliest days, interventions in places like Haiti, Bosnia, Colombia, East Timor and Kosovo — plus inherited missions in the Persian Gulf and Somalia — have served to widen the divide between Republicans and Democrats on how U.S. forces should be used abroad. By the time the Kosovo war began in 1998, Republicans in Congress were so unwilling to support the mission that the House voted against funding a ground war even as American pilots dodged Yugoslav SAM missiles. The Senate joined a few days later in a 48-48 tie on a resolution to support U.S. action in Kosovo.

The failure of Clinton’s team to bridge this gulf in the U.S. Congress led to constraints on the president’s options, and to some very mixed signals to the rest of the world. Allies and foes alike complained that U.S. intentions were often impossible to divine. This is not all bad, of course, in diplomacy, but being consistently inconsistent is unsettling to American allies. The lack of a consensus at home also deepened Washington’s dispute with the United Nations, often the only institution willing to intervene in smaller regional conflicts. With Clinton unable to win the support of Congress for actions under U.N. auspices, the bar for military action abroad rose precipitously.

Unilateral moves like the Kosovo war and the U.S.-British enforcement actions against Iraq were possible, but the United States lost much of its influence on the resolution of smaller wars in Africa and Asia as rebels and despots in both places saw clearly that Washington was not about to act.

The future in Asia

Perhaps the greatest question mark of the Clinton years hangs over his administration’s approach to China.

Politically divisive from the start (Clinton, remember, hung his 1992 rival George Bush with the label “coddler” of China’s dictators), by 2000 official U.S. policy was one of “engagement,” to the point where Washington helped usher China to the top table of global capitalism, the World Trade Organization. The concessions won in return for America’s backing are portrayed as a milestone by the outgoing administration and the best bet for forcing political liberalization on the last of the world’s communist giants.

Yet that rosy view is flatly rejected by a wide coalition of groups who regard open trade with China as inherently immoral for national security, religious, environmental or human rights reasons. What’s more, even if one agrees that economic liberalization and engagement is America’s best hope of encouraging democracy there, a series of fiascoes during the Clinton years badly undercut the administration’s leverage.

Included here would be domestic political scandals involving Chinese espionage at American nuclear labs, Chinese government money being used to fund Democratic campaigns in the 1996 election and the destruction of China’s embassy in Belgrade during the Kosovo war.

The invisible hand

One lasting change ushered in by Clinton in America’s dealings with the world is the elevation of economic policy to a top foreign policy concern. Clinton’s Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin had an unprecedented leading role in forging policy toward Asia’s “tiger” economies and in formulating responses to economic crises in Russia, Latin American and Indonesia.

Rightly surmising that the post-Cold War world had increased the power of financial markets at the expense of nation states, Clinton became a proponent of “incentive diplomacy.” Where a past president might have promised American warplanes or military advisers, Clinton’s administration promised economic aid and private investment guarantees in an effort to prod Israelis and Palestinians, Northern Ireland Protestants and Catholics, Bosnian Serbs, Muslims and Croats alike into peaceful coexistence.

Perhaps his most dramatic economic gamble overseas was his 1995 intervention to prop up Mexico’s faltering currency, a move taken over the strong opposition of the new GOP majority in Congress. With Rubin’s advice, Clinton tapped a national security emergency fund and persuaded Europe and Japan to throw in, a move that in retrospect may have staved off the complete collapse of Mexico’s economy and the waves of refugees the U.S. southwest would certainly have faced. Mexico’s subsequent repayment of the $20 billion loan with interest, and last year’s first-ever election of a Mexican president not connected with the longtime ruling party, the PRI, appears to further vindicate Clinton’s decision.

Clinton failed to win the Middle East peace agreement he pursued so actively, and he can show little dramatic progress in the effort to come to terms with Russia’s new realities or China’s emergence as a potential rival. Yet he helped stabilize America’s closest neighbor, shepherded NATO through a modernization and expansion, outlasted Milosevic and, arguably, kept Saddam Hussein contained. It’s a list of accomplishments that may not amount to a “legacy” in the league of Nixon’s opening of China or Truman’s launch of the Marshall Plan. But then, those men lived in far more interesting times.