Call it what you will — the world's first 3D nanoantenna or an invisibility cloak — but a new metamaterial created by Rice University scientists could hide objects from human sight.

By creating perfectly aligned dimples in a material, the scientists channeled specific wavelengths of light from many directions into one uniform direction.

"This falls into the broad class of metamaterials that have useful and unusual properties, like cloaking," said Naomi Halas, Rice University scientist and co-author of a paper describing the material in Nano Letters. "In a broader picture, you could do some very interesting things with this metamaterial."

The first "invisibility cloak," which hid objects from relatively long-wavelength radio waves, was created in 2006 by scientists from Duke University. Since then scientists have tried to create ever-smaller structures to manipulate ever-smaller wavelengths of light, with the goal of creating a true invisibility cloak that would hide objects in the visible spectrum of light.

According to Halas, this is the world's first truly 3D metamaterial -- a metamaterial being something that gets its trademark properties from its structure rather than its makeup.

Creating the first nanoantenna was relatively simple.

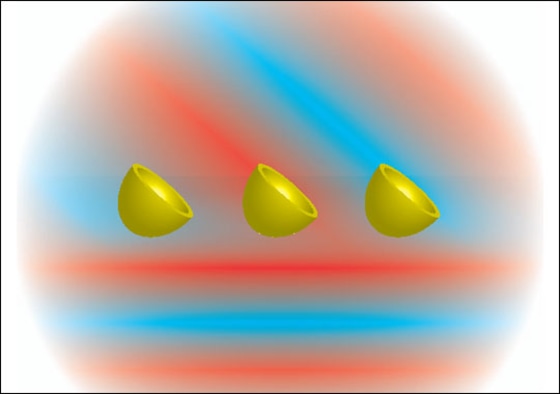

Scientists started with a layer of glass. Latex or plastic nanoparticles were sprayed over the glass at random. Gold particles were evaporated onto the nanoparticles at five different angles, creating 'nanocups.' A protective layer of acrylic was then poured over the top and cured for 36 hours to form a hard slab.

The nanocups are arranged in a repeating pattern, all angled in one direction. Any light that enters a nanocup is gathered and then emitted in the direction of that angle. Since no light is reflected back into an observer's eye, the nanoantenna-coated object is hidden.

"Think about the retro reflectors on stop signs," said Halas. "Those are basically microspheres that direct the light from your headlights back at you. This is the opposite. This would take the light and send it in another direction, hiding the stop sign from your sight."

Reflecting all the gathered light in one direction means that the nanoantenna acts kind of like a mirrored magnifying glass, concentrating the light at a particular point. Unlike a magnifying glass, however, it doesn't matter what angle the light enters; it all goes to the same point.

Practical uses for the nanoantenna go beyond hiding things.

Solar collectors reflect light on a single point, but to work at maximum efficiency they must be mechanically tilted to stay in line with the sun as it moves across the sky.

The new nanoantenna would concentrate light on a single point without having to mechanically tilt it, eliminating one of the biggest costs involved in solar panels.

"In a lot of solar cells, most of the light passes right though the material," said Halas. With the new 3D nanoantenna, "you could change the direction of the light so it propagates through the active regions of the solar cells to maximize [energy]."

Whatever the material is used for, scientists agree that this is the world's first truly 3D nanoantanna.

"Until now it has been difficult to build 3D shapes," said Gennady Shvets, a scientist at the University of Texas at Austin who studies metamaterials. "People used lithography to create essentially flat or planar structures, but those have their limitations."