The sun’s energy output has barely varied over the past 1,000 years, raising chances that global warming has human rather than celestial causes, a study shows.

Researchers from Germany, Switzerland and the United States found that the sun’s brightness varied by only 0.07 percent over 11-year sunspot cycles, far too little to account for the rise in temperatures since the Industrial Revolution.

“Our results imply that over the past century climate change due to human influences must far outweigh the effects of changes in the sun’s brightness,” said Tom Wigley of the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Most experts say emissions of greenhouse gases, mainly from burning fossil fuels in power plants, factories and cars, are the main cause of a 1.1-degree Fahrenheit (0.6-degree Celsius) rise in temperatures over the past century. But some scientists say the dominant cause of warming is a natural variation in the climate system, or a gradual rise in the sun’s energy output.

Based on satellite observations conducted since 1978, “the solar contribution to warming over the past 30 years is negligible,” researchers wrote in Thursday's issue of the the journal Nature.

The researchers also found little sign of solar warming or cooling when they checked telescope observations of sunspots against temperature records going back to the 17th century.

They then checked more ancient evidence of rare isotopes and temperatures trapped in sea sediments and Greenland and Antarctic ice, finding no dramatic shifts in solar energy output for at least the past millennium.

Sun judged not guilty

“This basically rules out the sun as the cause of global warming,” Henk Spruit, a co-author of the report from the Max Planck Institute in Germany, told Reuters.

Many scientists say greenhouse gases might push up world temperatures by perhaps another 5 degrees F (3 degrees C) by 2100, causing more droughts, floods, disease and rising global sea levels.

Spruit said a “Little Ice Age” around the 17th century, when London’s Thames River froze, seemed limited mainly to western Europe and so was not a planetwide cooling that might have implied a dimmer sun.

And global Ice Ages — such as the last one, which ended about 10,000 years ago — seem linked to cyclical shifts in Earth’s orbit around the sun rather than to changes in solar output.

No evidence on long-term time scales

“Overall, we can find no evidence for solar luminosity variations of sufficient amplitude to drive significant climate variations on centennial, millennial or even million-year time scales,” the report said.

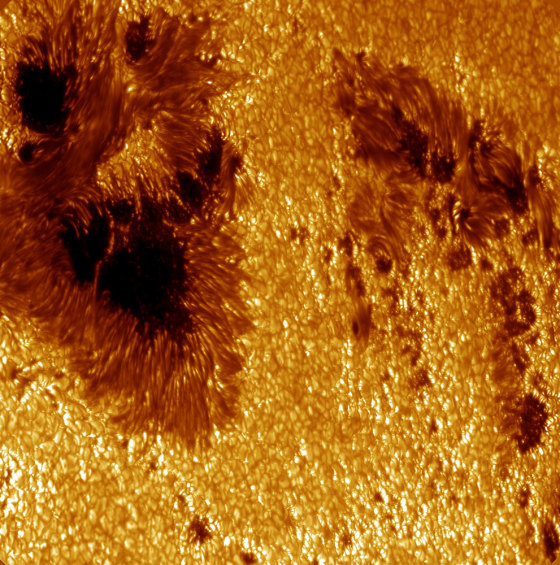

Solar activity is now around a low on the 11-year cycle after a 2000 peak, when bright spots called faculae emit more heat and outweigh the heat-plugging effect of dark sunspots. Both faculae and dark sunspots are most common at the peaks.

Still, the report also said there could be other, more subtle solar effects on the climate, such as from cosmic rays or ultraviolet radiation. It said those effects would be hard to detect.