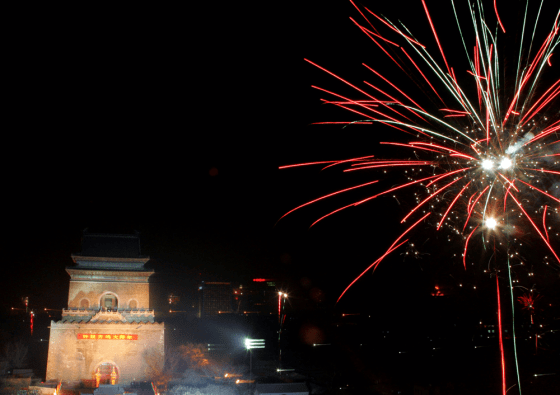

China marked the start of the Year of the Dog on Sunday with fireworks and dumplings, as the biggest holiday in the Chinese world reached a crescendo.

In Beijing, residents were allowed to set off fireworks and firecrackers in the city for the first time in 12 years, and used the opportunity with gusto, filling the sky into the early hours with brightly coloured explosions.

At midnight on Lunar New Year’s Eve in Shanghai, China’s richest and most cosmopolitan city, clouds of smoke and a rain of red wrappings obscured even the nearest buildings, while echoing explosions shook the windows.

Firecrackers are believed to scare off evil spirits and attract the god of wealth to people’s doorsteps.

Chinese will set off 1 billion yuan’s ($124 million) worth of fireworks and firecrackers over this year’s spring festival period, according to state media, as more than 200 cities lift restrictions on pyrotechnics.

A set of 16 “Venus Walker” fireworks, creating a satisfying burst of colour worthy of a small American town’s Fourth of July display, cost less than 100 yuan in Shanghai.

Elsewhere in China, President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao spent the Lunar New Year in the countryside, chatting with peasants about rural poverty and healthcare issues.

Hu visited the old revolutionary base of Yan’an in dusty, central Shaanxi province and joined villagers in a folk dance, while Wen went to the eastern province of Shandong and gave money to a farmer with a sick wife.

In previous years, Chinese leaders have spent new year with everyone from AIDS victims to coal miners, usually as a way of promoting a particular policy theme.

Dumplings and gold

Many Chinese saw in the new year eating dumplings that are supposed to symbolise wealth, because the pastry-wrapped parcels of meat and vegetables take the shape of gold and silver ingots of China’s imperial past.

And there are many traditional taboos over the spring festival. Crying on new year’s day means you will cry for the rest of the year, and washing hair is out as it signifies washing away good luck.

Likewise, the number “four”, which sounds like the word for “death”, is banned, and knives or scissors should not be used because they may cut off good fortune.

But for some, all the festivities and the commotion cannot erase the nostalgia.

“New Year isn’t as much fun as it used to be,” said Shanghai resident Lao Xu, whose childhood home was razed to make way for the glamorous skyscrapers of the Pudong business district.

“Back then, we all lived in smaller houses and everyone knew everyone else,” he said. “Now people live in apartments and stay out of each other’s business, and it isn’t as much fun any more.”

Indeed, some worry that New Year traditions are being lost in the country’s headlong rush to develop economically.

“It is being attacked by Western culture,” Henan University Professor Gao Youpeng wrote this week in the official Guangming Daily, issuing what he called a “declaration to protect Spring Festival”.

“More and more people, especially the young, have no time to consider the true meaning of the festival and prefer to celebrate the game-like revelry of Western holidays like Christmas and Velentine’s Day,” he wrote.