Apple took its turn in the privacy hot seat this week, but it was a short stay. Before the company could press-release its way out of trouble over its location-tracking iPhones, Sony grabbed that spotlight with a far more serious data transgression.

When Sony's PlayStation disaster distracted us from Apple's geolocation fiasco, we lost much more than 77 million accounts' worth of data. We lost a tremendous learning opportunity, a chance to focus on the greatest privacy question of our time, or perhaps any time:

Should we let corporations and governments know where we are all the time?

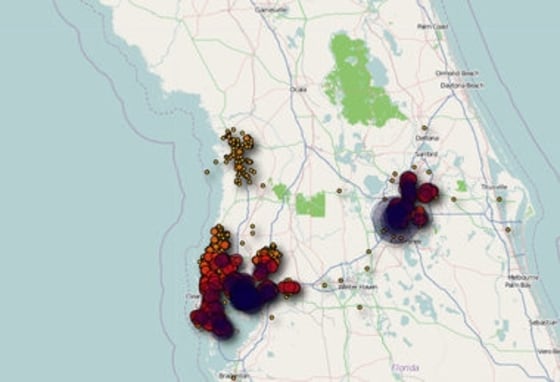

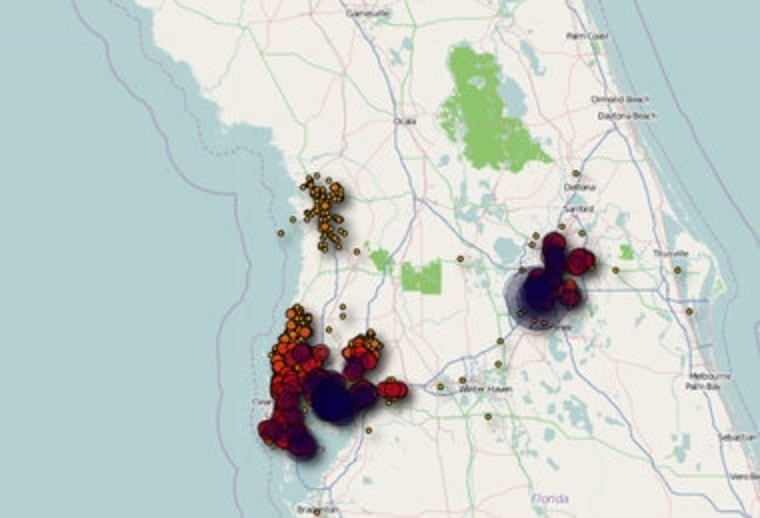

When researchers discovered last week that there was enough information in a file on most iPhones to determine the owner’s whereabouts dating back several months, disturbing location maps began appearing all over the Internet. But really, they were just visual representations of something most of us already knew deep inside: Cell phone companies know where we are all the time. We also know grocery stores track what we eat and that governments know when we drive through toll booths.

The problem is this: We've never talked about whether this is a good or a bad idea. We are all being tracked now, and our whereabouts logged. But what should we do about it?

Complex discussions about privacy are one thing. Allowing the world to know where you are, and to keep that information indefinitely, is another.Most of us shove these spooky thoughts out of our mind, until there's a news incident with just the right elements -- a big company that is cavalier with our data, secretly surveils us, misleads us or falls prey to a dramatic hack -- that we sit up and notice. Visualizations, like the Apple tracking maps we saw, help too.

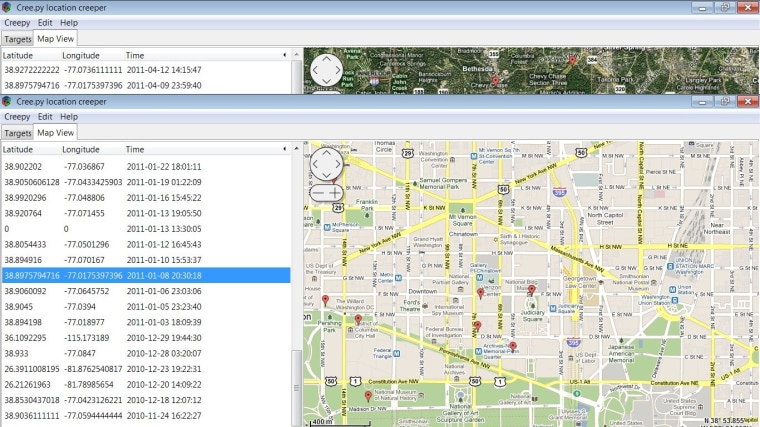

The concern usually only lasts for a day or so, but the issue remains: What rules should govern the capture and retention of location information? The maps generated through Apple's secret location file are no different than the map I generated recently using an app called Cree.py, which scours the Internet grabbing as much location data as it can from Targets.

If that's not enough to unnerve you, it should at least be enough to convince you that now is the time for this discussion. Geolocation-enabled software like Twitter, Facebook and Foursquare is all the rage. Computers can tell you lots of interesting things when they know where you are -- like where your friends are, or where there's a good deal on pizza. That's great.

The real problem is the retention of location information over time. Even if you completely trust individual companies like Apple not to abuse such information, you can't assume the culture of that firm will never change. More important, by now we should all know that no business can be trusted 100 percent to keep information out of hackers' prying hands. Meanwhile, cell phone providers basically admitted to Congress this week that they have no control over third-party software developers and what they do with location information. Maybe it doesn't bug you that a cell phone company and its partners knows where you've been for the past six months, but what about a random hacker?

There are serious political concerns with storage of this level of information. If a company has data on its computers, it can share it with another company; a law enforcement agency can get it; a lawyer with a court order can get it Meanwhile, if a hacker can get it, so can a foreign government. It’s not hard to imagine a scenario in which the Chinese government could learn the physical location of millions of Americans over time.

Apple was hit with a lot of flak this week for its relatively slow response to the crisis. The explanation that it didn't collect cell phone locations, but rather the location of nearby towers and hot spots (at this point, I'll repeat again for them -- some “more than 100 miles away") was meaningless. Obviously, anyone with access to the file on the iPhone could figure out where you were for months, and that's terrible. The firm says long-term storage of the information was essentially a bug that will be fixed. Sure, but when might a similar bug occur?

On the other hand, if you sensed from Apple -- and Apple sympathizers -- a bit of, "everyone does this, why is this such a big deal?” that's because they're right. It's true that location information greatly helps their network function. Anyone who's ever turned on a GPS and waited five minutes for the gadget to get a "fix" can appreciate the enhancement Apple was implementing. Plenty of other companies do collect and use detailed location information about us. Many will tell you they “anonymize” the information, they have strict policies about how it is used and stored, that they always get users’ permission before collecting it, that they secure it, yadda, yadda, yadda. The Apple incident shows that location information is toxic, and the consequences of its collection can be very hard to control.

Here's the problem. Consumer data -- particularly location data -- is the nuclear waste of the digital age. Companies collect as much of it as they possibly can, and keep it as long as they can. They can't help themselves. But the half-life of personal information is infinity. Long after the data is useful, it hangs around like so many spent fuel rods, waiting for hackers to steal it or someone to accidentally load it onto a USB stick. There are hundreds of examples of this every year.

Apple may now be shrinking the time it stores location data from months to seven days, but it's doing so out of the goodness of its heart. It could reverse this decision – or another bug could appear that causes longer-term storage again. The only consequence would be another embarrassing news story.

That’s lunacy. Laws – not promises -- are needed to codify what location information can be used for, and how long it can be stored.

The law governing health care personal information law, HIPPA, has many flaws, but it served one important purpose. HIPPA created a mystique around health care information, a culture of very conservative information sharing among health care workers. The seriousness with which doctors, nurses, dentists, etc., take HIPPA's secrecy policy is striking. I have several friends who volunteer at hospitals and are deathly afraid of talking about patients in even the most general terms.

Those who collect location information should be forced into a culture at least that sober. Apple should know, for example, that if it ever stores a year of location information anywhere again, there will be consequences that will immediately impact the company’s bottom line, and its stock price.

I know many people really believe they have nothing to hide. Clearly, millions of Internet users are comfortable broadcasting their location to the world, and can't imagine any serious consequences coming from it. They might be right. It's certainly their right to take advantage of the fun things location-enabled software can do, and no one wants to take that away from them.

I would respectfully argue that this is unsophisticated thinking, however. Today's neat location perk is a scant trade-off for unknown consequences that might come 5, 10, even 25 years from now. I think most people, confronted with the reality that a foreign government might build a case against them someday based on detailed information about their whereabouts, would come to more moderate conclusions about what they have to hide. How easy would it be to determine your religion, your employer, perhaps even your political views, from an intelligent search of your location information? Why should that ever be possible?

It's crazy that we're walking into a world where companies and governments know where we are, and where we’ve been, without guiding principles to save us from ourselves. Location information should be deleted immediately after it is not needed for the exact purpose it was collected for.

We need a law of the land before we permanently lose the idea that where we are, and where we've been, is a sacred secret.

COMMENTS BEGIN BELOW

NOTE: Red Tape comments are aggressively moderated. Readers desire a thoughtful discussion of the issues, and that's what we aim for. Comments that include inappropriate language, personal attacks on others, or are off-topic will be hidden, and writers risk a ban.

TO COMMENT ANONYMOUSLY: E-mail [email protected]. Your comment will be reviewed and posted by msnbc.com, noting the anonymity request.

TO COMMENT WITHOUT A FACEBOOK LOGIN: E-mail [email protected]. Your comment will be reviewed and posted by msnbc.com, attributed to you.